William Horwood: The Willows in Winter (1993)

William Horwood: The Willows in Winter (1993)•

William Horwood (1944- )

William Horwood (1944- )William Horwood: The Willows in Winter (1993)

[Finally Books - Hospice Bookshop, Birkenhead - 31/3/25]:

William Horwood. The Willows in Winter: The Sequel to the Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Patrick Benson. 1993. New York: St Martin's Press, 1994.

Imitation, they say, is the sincerest form of flattery. If that's truly the case, then Kenneth Grahame must be feeling very flattered indeed in the next world. Not only does his only novel, The Wind in the Willows, remain in print after more than a century, but it still appears to be capable of spawning sequels, commentaries, annotated and illustrated editions at a remarkable rate.

- Imitators (1929-2024)

- Annotators (2009)

- Illustrators (1913-2021)

- Commentators (1908-2025)

- Bibliography

Once upon a time these processes could be kept more or less under control. A. A. Milne's 1929 adaptation of The Wind in the Willows into a stage play had to be licenced by Kenneth Grahame himself. It was very popular, and has been revived many times since.

J. R. R. Tolkien was not so sure about it. As he says in his famous essay "On Fairy-Stories" (1947):

It is ... remarkable that A. A. Milne, so great an admirer of this excellent book, should have prefaced to his dramatized version a "whimsical" opening in which a child is seen telephoning with a daffodil. Or perhaps it is not very remarkable, for a perceptive admirer (as distinct from a great admirer) of the book would never have attempted to dramatize it.However, as Martin Crookall reminds us in an informative 2020 article about the Willows on his blog Author For Sale (subtitled "a transparent attempt to promote a writing career"):

... The play is, on the lower level of drama, tolerably good fun, especially for those who have not read the book; but some children that I took to see Toad of Toad Hall brought away as their chief memory nausea at the opening. For the rest they preferred their recollections of the book.

The copyright law in the UK and across most of the world is that copyright in a work endures for the author’s lifetime plus seventy years, after which it, its contents and characters go into the Public Domain.Since he died in 1932, Kenneth Grahame's copyrights were not affected by this revision to the law. Accordingly, in 1983 his work became fair game to imitators and their publishers. One of the first to take advantage of this was a certain Dixon Scott. Crookall explains:

This wasn’t always so: until 1985, the rule was life plus fifty years. And the law was changed for the benefit of Great Ormond Street Children’s Author. The playwright and author James Barrie had willed to Great Ormond Street the royalties on his massively popular work, Peter Pan, amounting to a vast income down the years.

But Peter Pan was shortly to come out of copyright and, so as to preserve that income for a foreseeable period, Parliament enacted the change.

According to the author’s blurb, Scott was an already published author whose first novel ... Jolly Jack Tart ... published in 1974, was about his wartime experiences in the Navy. He’s also described as a Wind in the Willows lover who himself lives by a river. This is all we know about Scott: everything else must be gleaned from the book itself.Nevertheless, Crookall's verdict is basically favourable:

Unlike the later, official sequels, four of them, produced by William Horwood, Scott’s book is simple, straightforward and surprisingly effective in giving us just a few more adventures of Mr Toad, the Water Rat, the Mole, the Badger and the Otter. Scott is indeed a lover of the original book, and this shows in every line. He does everything he can to create and maintain a light, consistent atmosphere, showing these familiar characters in the same light as Kenneth Grahame, and at no point did I feel anything approximating to a wrong note (whereas with Horwood’s first attempt, The Willows in Winter, I thought the first chapter got things so badly wrong that I refused to read any more of the book or any of its sequels).Since Dixon Scott and William Horwood made their respective attempts to perpetuate the hijinks on the riverbank, though, the spinoffs have kept on coming thick and fast. Here's a brief (undoubtedly incomplete) list of the examples I've located so far:

1: [1983] - Dixon Scott: A Fresh Wind in the Willows: A Sequel to The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Jonathon Coudrille (London: Heinemann)

"Presents the further adventures of Ratty, Mole, Toad, and Badger, four animal friends who live along a river in the English countryside."

2: [1993-99] - William Horwood: Tales of the Willows. 4 vols. Illustrated by Patrick Benson (London: HarperCollins)

- The Willows in Winter (1993)

- Toad Triumphant (1995)

- The Willows and Beyond (1996)

- The Willows at Christmas (1999)

"In an act of homage and celebration, William Horwood has brought to life once more the four most-loved characters in English literature: the loyal Mole, the resourceful Water Rat, the stern but wise Badger, and, of course, the exasperating, irresistible Toad. The result is an enchanting, unforgettable new novel, enlivened by delightful illustrations, in which William Horwood has recaptured all the joy, magic, and good humor of Grahame's great work - and Toad is still as exasperatingly lovable as he ever was."

3: [2012] - Jacqueline Kelly: Return to the Willows. Illustrated by Clint Young (London: Henry Holt and Co.)

"Mole, Ratty, Toad, and Badger are back for more rollicking adventures in this sequel to The Wind in the Willows. With lavish illustrations by Clint Young, Jacqueline Kelly masterfully evokes the magic of Kenneth Grahame's beloved children's classic and brings it to life for a whole new generation."

4: [2017-18] - Tom Moorhouse: The New Adventures of Mr Toad. Illustrated by Holly Swain (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- A Race for Toad Hall (2017)

- Toad Hall in Lockdown (2017)

- Toad in Troubled Waters (2018)

- Operation Toad! (2018)

"Teejay (which stands for Toad Junior), Mo and Ratty are exploring the ruined grounds of Toad Hall. After falling into a tunnel they discover ... someone in the ice house. It turns out to be Mr Toad and the children have found him in the nick of time: Wildwood Industrious (the shady operation run by the descendants of the Stoats and Weasels) is on the brink of claiming legal ownership of Toad Hall. With outrageous antics from Mr Toad, action-packed adventure from the start, and stylish two-colour illustrations from Holly Swain that capture all the comedy, this is a fantastic package for young readers."

5: [2019] - Frederick Gorham Thurber: In the Wake of the Willows: A Sequel to Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Amy T. Thurber (USA: Cricket Works Press)

"A New World version of a classic, set on a New England coastal estuary in the 1920's. This is a story about the denizens of a very special river. For like their relatives on the other side of the ocean, this river had its own Rat, Mole, Badger, Otter, and Weasel clans.

When a spooky nocturnal creature starts terrorizing the riverfront, Mr. Rat’s clever daughter sets to work solving the mystery and unmasking the culprit. But that is only the beginning of the intrigue and adventure one eventful summer.

This lyrically-written book features a mysterious Native American prophesy, a suspected sea monster, a scavenger hunt with a surprising twist, persnickety weasels, a mysterious clue etched on a piece of birch bark, some hilarious hijinks by Mr. Toad’s son, a chatterbox bobolink, a devastating hurricane, a heroic rescue, a liberal sprinkling of gentle humor, nautical adventures in wooden boats, some historical fiction, an unusual square dance with fireflies, a campfire on the beach at night watching shooting stars, some scalding Advanced Praise, an outrageously conceited poem by Mr. Toad, and an snarky interview by the author.

This story is set against the rural backdrop of coastal New England almost a century ago. All the natural history and science in this book is accurate and will inspire young readers to learn more. Most of the locations, boat names, and historical events are accurate for the times."

6: [2024] - Colin Childs: Willows Rewilded (Independently published)

"Toad Hall, derelict and empty for a century, sees the return of the impecunious Horatio Toad and his six wives to the ancestral home.

In need of cash, Horatio has leased out his estate and formed a partnership with oddball rewilder Georges Montgolfiere, who needs the land more than he needs Horatio. Tensions mount as Horatio’s vision of an animal-based theme park, replete with zipwires and gift shops, is diametrically opposed to Montgolfiere’s purist sensibilities.

Meanwhile, a bemused Mole surfaces not to a 'silent spring', as Montgolfiere contends, but to a fractious one. Badger is apoplectic; someone or something has pillaged his truffle beds. Ratty, now vegan and identifying as a vole, is suffering from alopecia while the translocated otter family copes with indigestion and sewage.

A 'New Wild Order' will emerge, but the outcome will be beyond Montgolfiere’s wildest imaginings. The rewilder will discover the rewilded have their own plans.

Willows Rewilded is a humorous slant on rewilding and contemporary politics with some adult content."

7: [2024] - Emilia Ermine: The Willows Chronicles: A sequel to The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Graham [sic]. The Willows series. 3 vols. Ed. David Bouchier (Independently published)

- Part One: A sequel to The Wind in the Willows (March 23, 2024)

- [with Sally Stoat] The Saga Continues: A sequel to the sequel to The Wind in the Willows (February 16, 2024)

- The New Wild World {November 21, 2024)

"The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame was and is one of the most popular books for children ever published. He never wrote a sequel. Other authors have tried, but none had access to the original source material [? - ed.] ... As a result, no later version has captured the joy, the gentleness, and above all the humor or the original.

The Willows Chronicles takes us back to that arcadian corner of England as it was before the First World War, where we can enjoy the further adventures of Mole, Water Rat, Badger and the self-important Mr. Toad. As the seasons pass along the riverbank there is never a dull moment. Toad Hall is haunted, Badger shares his accidental library, Water Rat becomes (very briefly) a steamboat captain, Toad gets involved in a wild car chase, and Mole opens an underground restaurant."

How did Siegfried Sassoon put it, in one of his more trenchant war poems? "O Jesus, make it stop!"

What should we call it? Fan-fiction, perhaps? Willows-kitsch? Whatever sobriquet we choose for them, I note an acceleration in new Willows sequels over the past few years. Most of the later examples are defiantly self-published, but earlier on there was definitely a market for such books.

A number of readers seem to prefer Dixon Scott's A Fresh Wind in the Willows to the more elaborate "official" continuations by mole-enthusiast William Horwood. Zeta T., for instance, echoes Martin Crookall's strictures on the latter (quoted above):

Very good. I found the final chapter the best. A bit lighter on the drama and humans than the Horwood sequels. Love that a lot of other critters made appearances and plenty of Otter, too!At the risk of being declared an old fogey, I have to say that, having now painstakingly worked my way through The Willows in Winter, I'm inclined to agree with Crookall and Zeta T.'s reservations about Horwood's work. It is, admittedly, clearly intended for a rather younger audience than myself, but even so it seems to me to lack the ... what? magic? mystery? - narrative logic, perhaps, inherent in Grahame's masterpiece.

For the rest, I'm forced to side with that grumpiest of spoilsport critics, Tolkien himself. All of these sequels may be

... on the lower level of drama, tolerably good fun, especially for those who have not read the book; but some children [presumably his own - ed.] ... brought away as their chief memory nausea ... For the rest they preferred their recollections of the book.

Which brings us to another level of Willows-iana: the annotated editions. I've already written a certain amount about this in my posts on the Norton Annotated Editions and Harvard Annotated Classics series.

In particular, I discussed the strange coincidence - if it was a coincidence - which led to these two publishers issuing their two rival editions at the same time:

Two annotated versions appeared within months of each other - more or less in the centenary year of the Kenneth Grahame's immortal masterpiece. For all its faults, I'd have to award the crown to Annie Gauger's for sheer inclusiveness, but there is a quiet dignity - though perhaps too great a dependence on dictionary definitions of fairly familiar terms - to Seth Lerer's Belknap Press edition:

- Kenneth Grahame. The Annotated Wind in the Willows. 1908. Ed. Annie Gauger. Introduction by Brian Jacques. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2009.

- Kenneth Grahame. The Wind in the Willows: An Annotated Edition. 1908. Ed. Seth Lerer. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

"Creator and editor of The Annotated Wind in the Willows (published by Norton & Co.), Annie Gauger studied at Oxford University and spent over a decade researching Grahame’s papers in the Bodleian Library. She was also a fellow at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas. She is a member of the Kenneth Grahame Society and has appeared on NPR and the BBC."A 2023 talk she gave at the Barrow Bookstore in Concord, Massachusetts, (in 2023) was billed as follows:

Calling all Wind in the Willow fans! Paddle in from the river; walk from the wild woods; or steer your race car to Concord’s Barrow Bookstore and step into author Annie Gauger’s sharing of the stories behind Kenneth Grahame’s beloved novel.I think that gives you a reasonable taste of the character of her book. It's unrestrained, over the top, feverishly detailed. At times it may even stray over the borders of good taste, but if you want information - like the secret agents in that classic British TV serial The Prisoner - this is the book for you.

Annie will describe how Grahame came to write the novel that began as a bedtime story and evolved over a series of letters he wrote to his son, Alastair. From topics such as early motorcar etiquette, eccentric Dukes and underground tunnels, and inspirations for the beloved characters, Annie’s research brings this classic to life and honors its creator.

"Seth Lerer ... is an American scholar and Professor of English. He specializes in historical analyses of the English language, and in addition to critical analyses of the works of several authors, particularly Geoffrey Chaucer. He is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Literature at the University of California, San Diego, where he served as the Dean of Arts and Humanities from 2009 to 2014. He previously held the Avalon Foundation Professorship in Humanities at Stanford University. Lerer won the 2010 Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism and the 2009 National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism for Children’s Literature: A Readers’ History from Aesop to Harry Potter."As you can see, Dr Seth Lerer is a very different kettle of fish. The pitch for his own annotated edition stresses its scholarly credentials:

Now comes an annotated edition of The Wind in the Willows by a leading literary scholar that instructs the reader in a larger appreciation of the novel's charms and serene narrative magic. In an introduction aimed at a general audience, Seth Lerer tells us everything that we, as adults, need to know about the author and his work. He vividly captures Grahame's world and the circumstances under which The Wind in the Willows came into being. In his running commentary on the novel, Lerer offers complete annotations to the language, contexts, allusions, and larger texture of Grahame's prose.I like that phrase: "everything that we, as adults, need to know about the author and his work." But who's to decide just what we need to know? Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Who will watch the watchmen? It's no accident that Alan Moore chose that phrase as the epigraph for his own anti-establishment classic Watchmen.

Lerer's is good, sober-sided work. There's no doubt about that. And it is, perhaps, more in tune with Kenneth Grahame's own restrained, self-effacing temperament than Gauger's manic extravagance.

It comes down to a question of taste, really. The book doesn't really need either Gauger or Lerer to create its full effect. When I first read it, it was in a little hardback edition without illustrations or any other accompaniments to the bare text. It made no difference. From the very first lines about Mole's spring-cleaning, I was hooked.

•

Carolyn Hares-Stryker: The Illustrators of the Wind in the Willows: 1908-2008 (2009)

Carolyn Hares-Stryker: The Illustrators of the Wind in the Willows: 1908-2008 (2009)

Illustrators

(1913-2021)

(1913-2021)

Which may, perhaps, serve as an introduction to the next fork in this labyrinth: the illustrators. Interestingly enough, as "Read Aloud Dad" explains in his 2015 blogpost "The Wind in the Willows - Some of The Best Illustrated Children's Editions":

Over the past 100+ years, more than 50 different illustrators have adorned the pages of this children's classic with their own visions of the story.Carolyn Hares-Stryker puts the figure somewhat higher, at "over 90 artists." It seems a bit impractical to try and hunt out that many editions, so I'll stick here to a few of the acknowledged highlights:

1: [1913] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Paul Bransom (New York: Scribners)

Grahame himself liked these illustrations and wrote back to his agent, in 1913: "I was much relieved to find no bowler hats or plaide waistcoats. And I like the drawings, too, very much. They have charm and dignity and good taste."

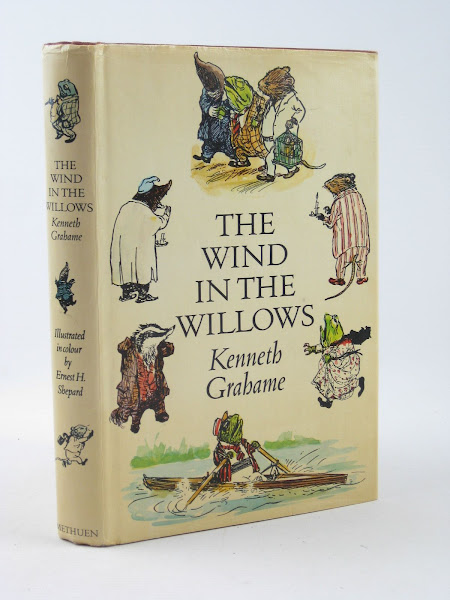

2: [1931] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard. Coloured 1959 (London: Methuen)

Edwin Ahearn remarks: "... by contrast with his relationship with Milne, it was a warm collaboration, and Shepard was always proud that the author on seeing his sketches, chuckled, and commented 'I'm so glad you made them real!'."

3: [1940] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham (London: The Limited Editions Club)

Italian online commentator Shelidon explains: "... it’s the absolute last book [Rackham] worked on before he died: his edition was issued posthumously and has a troubled editorial history. Rackham had been a long-time fan of the book and had always regretted having to turn down the invitation to illustrate it, almost thirty years before this second opportunity arose. He was already ill when publisher George Macy offered him to illustrate it, and he was moved by the suggestion, and immediately started working on it."

4: [1980] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Michael Hague (New York: Henry Holt & Co.)

"... I’m not completely sure his particular style, which I generally adore, is suitable for the charming countryside that is meant to surround the Wind in the Willows, but his indoor scenes (if we can rightfully say 'indoor' giving the particular circumstance) are absolutely amazing." - Shelidon

5: [1983] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows. Pictures by John Burningham (Harmondsworth: Kestrel Books)

"... A handsome new edition with the characters sensitively portrayed and the action evocatively and faithfully depicted by the 1963 winner of the Kate Greenaway Medal."

6: [1999] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Inga Moore (London: Walker Books)

"Inga Moore's illustrations are impossibly amazing" - Read Aloud Dad.

7: [2021] - Kenneth Grahame: The Wind in the Willows. Illustrated by Roger Ingpen (London: Welbeck Children's Books)

"Ingpen's drawings are utterly compelling" - Michael Morpurgo.

•

Mind you, these seven examples are just the tip of the iceberg, There are many, many others - among them:

Charles Van Sandwyk's recent illustrations for the Folio Society; Chris Dunn's 2013 French language edition, now available in English;

not to mention these supremely evocative Beverley Gooding illustrations from way back in the 1970s:

Which are my favourites amongst all these beautiful pictures? I grew up on E. H. Shepard, so his versions of the characters are, for me, canonical and inescapable. But then, as I commented above, I first read the book in an unillustrated edition, so I don't actually regard any of them as strictly necessary to its effectiveness.

Of all the others, I'm surprised to realise that it's John Burningham who most appeals to me now. He seems to me to have got closest to the essence of the book - without either sentimentalising it or burying it in bewildering layers of detail.

I was initially quite hostile to Arthur Rackham's knobbly, almost threatening images - but they've grown on me over the years. The truth is that I like all of the efforts included above. The fact that the book doesn't need illustrations somehow legitimises the existence of so many different artists' visions, bound up in so many warring editions by rival publishers over the past century and a bit.

•

W. B. Yeats: The Wind Among the Reeds (1899)

W. B. Yeats: The Wind Among the Reeds (1899)

Commentators

(1929-2024)

(1929-2024)

"We are not concerned with the very poor. They are unthinkable,

and only to be approached by the statistician or the poet."

- E. M. Forster, Howards End (1910)

It's interesting to learn that The Wind in the Willows was - up to a week or so before publication day - entitled The Wind in the Reeds. Had it not been for a perceived clash between this and W. B. Yeats's turn-of-the-century poetry collection The Wind Among the Reeds, we'd now be debating the significance of "reeds" rather than "willows" in the genesis of Grahame's book.

"Reeds" would make more sense of the crucial chapter "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn," which is regarded by many readers as extraneous to the children's fantasy ethos of the rest of the book, but which certainly serves to link Grahame to his 1890s, Yellow Book roots. Pan-pipes are, after all, traditionally made of reeds.

Pan had a symbolic significance for fin-de-siècle writers which he hadn't held since the days of Neoplatonic emperor Julian the Apostate. Arthur Machen's "The Great God Pan" (1894); Algernon Blackwood's "The Touch of Pan" (1907) - his terrifying story "The Willows" appeared in the same year; E. M. Forster's "The Story of a Panic" (1911); not to mention J. M. Barrie's own Peter Pan (1904), all share a vision of Pan as a living entity, actively working against the assumptions of conformist, industrial civilisation.

The little animals who encounter him in all his glory in Grahame's book are not permitted to retain the memory of what they have seen - but the spirit of reverence it creates in them remains.

This idea is taken up more crudely by Grahame's follower Denys Watkyns-Pritchard ("BB"), who uses Pan as a kind of deus ex machina to extract his gnome protagonists from awkward situations in his children's novels The Little Grey Men (1942) and its sequel Down the Bright Stream (1948).

So, if we see the neopaganism which suffuses Grahame's early essay collection Pagan Papers as one of the main threads which go to make up the tapestry of The Wind in the Willows, then I think we would have to take the next of these threads as the idea of talking animals. J. R. R. Tolkien is, again, our most insightful guide on such matters. Here's another quote from his classic essay "On Fairy-Stories":

Beasts and birds and other creatures often talk like men in real fairy-stories. In some part (often small) this marvel derives from one of the primal “desires” that lie near the heart of Faërie: the desire of men to hold communion with other living things. But the speech of beasts in a beast-fable, as developed into a separate branch, has little reference to that desire, and often wholly forgets it.So what exactly is a beast-fable?

But in stories in which no human being is concerned; or in which the animals are the heroes and heroines, and men and women, if they appear, are mere adjuncts; and above all those in which the animal form is only a mask upon a human face, a device of the satirist or the preacher, in these we have beast-fable and not fairy-story: whether it be Reynard the Fox, or The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, or Brer Rabbit, or merely The Three Little Pigs."A mask upon a human face' - like it or not, that is what Mole, Rat, Toad, Otter and the others really are. But it's also important to note that:

There is no suggestion of dream in The Wind in the Willows. “The Mole had been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little house.” So it begins, and that correct tone is maintained.Neopaganism, beast-fable - what, then, is the third strand in Grahame's epos?

Well, for this I'll have to refer you to my old Edinburgh professor Wallace Robson's celebrated essay about The Wind in the Willows (reprinted in his 1983 collection The Definition of Literature and Other Essays).

I mentioned his probing of the social attitudes behind Grahame's novel in a previous post on classic children's books. In particular, I commented there on the accuracy of his analysis of:

the class values that underlie it: the proletarian weasels' attempt to encroach on the inherited domains of Toad, the local squire, who has to be upheld by our heroes, Mole, Rat and Badger, despite their own contempt for Toad's foolish and criminal antics.Toad might be a cad and a bounder, but he's still "one of us", a gentleman - unlike the savage, underclass inhabitants of the Wild Wood. It is, in effect, an expression of the same turn-of-the-century class anxiety which underlies Jack London's The People of the Abyss (1903), and the Eloi and Morlocks in H. G. Wells's The Time Machine (1995).

In both of those cases, London's and Wells's socialist beliefs lend their narratives an indignant rather than a nostalgic tone. Kenneth Grahame, though, ex-Secretary of the Bank of England, was not exactly a friend to anarchy and social disorder.

In 1903, Grahame had a narrow escape when a man entered the Bank of England and took three shots at him with a revolver, missing each time. The man, George Frederick Robinson, was overpowered and arrested. After a trial at the Old Bailey in which he was found guilty but insane, he was sent to Broadmoor Hospital. Grahame never completely recovered from the trauma and it may have contributed to his early retirement from the Bank.The Wind in the Willows was published in 1908, four months after the author's resignation from the Bank. It's hard to avoid the conclusion that at least some of his indignation at the attempted proletarian revolution undertaken by the stoats and the weasels from the Wild Wood was heightened by this abortive assassination attempt.

For all the attempts to paint it as an idyllic, a-political book, The Wind in the Willows does need to be situated in its original social and historical context if it is to be fully understood. As well as a masterpiece of escapism, it also constitutes the last gasp (almost) of the Squirearchy.

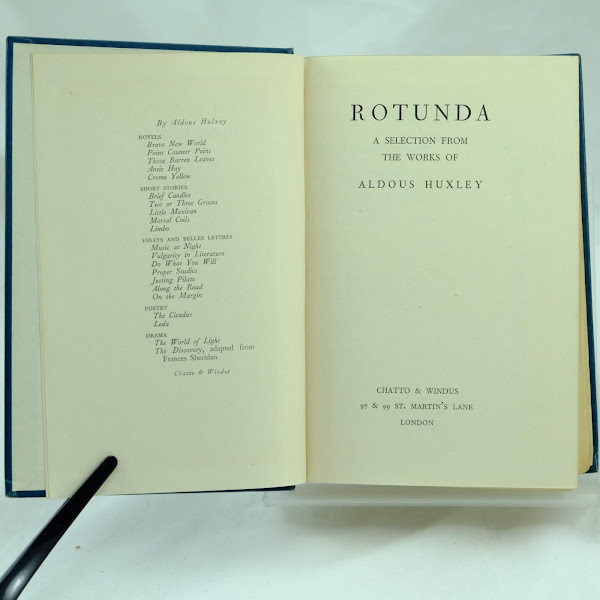

In an earlier discussion of the omnibus volume pictured above, I quoted its interesting 'Prefatory Note' (by the publisher, not the author, who died before its appearance):

It would have been possible to include in this collection Kenneth Grahame's book of essays, Pagan Papers, which appeared in the National Observer under W. E. Henley's editorship and won for him many warm admirers; and also his fantasy, The Headswoman; but on careful consideration it was decided that these two works were in a key so different from The Golden Age, Dream Days, and The Wind in the Willows that their presence here would be a mistake.It's hard to avoid the conclusion that this omission is an early attempt to guard Grahame's literary reputation from any suggestions of controversy.

I remarked at the time that his publishers may have been:

right in judging that the inclusion of a collection of lukewarm essays from the 1890s and a rather macabre fantasy would not have assisted them in reaching a target audience of children and their doting parents.Which is all very well. But Grahame's work is more complex and interesting than that, and it would probably have been better to acknowledge as much even at this early stage in the growth of his mystique.

So, if you've made it this far in this little discussion of the Willows and various select strands of Willowsiana, what would I like you to conclude from it?

- First of all, though I doubt there's any great harm in it, it might be nice if people concentrated on concocting their own fantasy worlds rather than freeloading on Kenneth Grahame's. Who knows, there may still be a lot more to be said about life on the river bank, but I haven't detected much evidence of that in the various sequels I've sampled to date: and that includes William Horwood's.

- Secondly, I'm not sure there's a need for any more annotated editions of the Willows. The two existing ones seem quite sufficient to me. Perhaps revised and enlarged editions of Gauger's and Lerer's work may be required at some point, but not unless there are some major new discoveries in Kenneth Grahame land.

- Thirdly, while there's certainly a superfluity of illustrated editions of The Wind in the Willows, given that several of the most accomplished examples have appeared in the last few years, it's hard to sustain an objection to them. There may be some mediocre or irritating ones, but for the most part they remain a delight!

- Fourthly, the world of scholarship is not really in the habit of putting a full-stop to any line of inquiry, fruitful or not. We can therefore look forward to many more essays and treatises on odd aspects of the Willows in the times to come - not to mention new biographical studies of poor old Grahame and his fey wife Elspeth and their half-blind, tortured son Alastair ("Mouse"), for whom the book was written in the first place. It's harmless (for the most part). It promotes full employment. And there are definitely far less life-enhancing texts one could concentrate on.

“Beyond the Wild Wood comes the Wide World,” said the Rat. “And that's something that doesn't matter, either to you or me. I've never been there, and I'm never going, nor you either, if you've got any sense at all. Don't ever refer to it again, please."

Books I own are marked in bold:

-

Essays:

- Pagan Papers (1894)

- Pagan Papers. 1893. London: John Lane The Bodley Head Limited, 1898.

- Paths to the River Bank. Ed. Peter Haining (1983)

- Paths to the River Bank: The Origins of The Wind in the Willows. From the Writings of Kenneth Grahame. Ed. Peter Haining. Illustrated by Carolyn Beresford. London: Souvenir Press, 1983.

- The Golden Age (1895)

- The Golden Age. 1895. With Illustrations and Decorations by Ernest H. Shepard. 1928. London: John Lane The Bodley Head Limited, 1948.

- Included in: The Kenneth Grahame Book: The Golden Age; Dream Days; The Wind in the Willows. 1895, 1898, 1908 & 1932. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1933.

- Included in: The Golden Age and Dream Days. 1895 & 1898. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. Foreword by Naomi Lewis. London: The Bodley Head, 1962.

- The Headswoman (1898)

- Dream Days (1898)

- Dream Days. 1898. With Illustrations and Decorations by Ernest H. Shepard. 1930. London: John Lane The Bodley Head Limited, 1950.

- Included in: The Kenneth Grahame Book: The Golden Age; Dream Days; The Wind in the Willows. 1895, 1898, 1908 & 1932. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1933.

- Included in: The Golden Age and Dream Days. 1895 & 1898. Illustrated by Charles Keeping. Foreword by Naomi Lewis. London: The Bodley Head, 1962.

- The Wind in the Willows (1908)

- The Wind in the Willows. 1908. Illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard. 1931. Coloured illustrations. 1959. London: Methuen, 1969.

- Included in: The Kenneth Grahame Book: The Golden Age; Dream Days; The Wind in the Willows. 1895, 1898, 1908 & 1932. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1933.

- The Wind in the Willows. 1908. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Introduction by A. A. Milne. 1951. London: Methuen Children’s Books, 1973.

- The Wind in the Willows. 1908. Pictures by John Burningham. Kestrel Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- The Wind in the Willows: An Annotated Edition. 1908. Ed. Seth Lerer. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

- The Annotated Wind in the Willows. 1908. Ed. Annie Gauger. Introduction by Brian Jacques. New York & London: W. W. Norton, 2009.

- The Reluctant Dragon. 1898. Illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard (1938)

- Bertie's Escapade. 1944. Illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard (1945)

- First Whisper of "The Wind in the Willows". Ed. Elspeth Grahame (1944)

- First Whisper of ‘The Wind in the Willows’. Ed. Elspeth Grahame. 1944. London: Methuen, 1946.

- Blount, Margaret. Animal Land: The Creatures of Children's Fiction. London: Hutchinson & Co (Publishing), 1974.

- Carpenter, Humphrey. Secret Gardens: A Study of the Golden Age of Children’s Literature. 1985. London: Unwin Paperbacks, 1987.

- Green, Peter. Kenneth Grahame: 1859-1932. A Study of His Life, Work and Times. London: John Murray (Publishers) Ltd., 1959.

- Green, Peter. Beyond the Wild Wood: The World of Kenneth Grahame. 1959. Exeter, Devon: Webb & Bower (Publishers) Limited, 1982.

- Prince, Alison. Kenneth Grahame: An Innocent in the Wild Wood (1994)

- Wullschläger, Jackie. Inventing Wonderland: The Lives of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, J. M. Barrie, Kenneth Grahame, and A. A. Milne (2001)

Fiction:

Letters & Journals:

Secondary:

•

- category - Children's Books: Fiction