Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell: The From Hell Companion (2013)

Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell: The From Hell Companion (2013)•

Alan Moore (1953- )

Alan Moore (1953- ) Eddie Campbell (1955- )

Eddie Campbell (1955- )Moore & Campbell: The From Hell Companion (2013)

[Hospice Shop, Silverdale - 24/7/24]:

Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell. The From Hell Companion. Foreword by Charles Hatfield & Craig Fischer. Marietta, GA: Top Shelf Productions / London: Knockabout Comics, 2013.

•

The Perils of Psychogeography

Alan Moore's graphic novel From Hell ... which postulates a "secret history" based on Masonic lore behind the Jack the Ripper murders, and Peter Ackroyd's novel Hawksmoor (1985), which spins a similar mythology around the strange set of churches built by Nicholas Hawksmoor after the Great Fire of London, draw heavily on Iain Sinclair's work, as well as on predecessors as various as William Blake, Arthur Machen, and Thomas de Quincey.When my colleague Ingrid Horrocks and I were putting together a module on Creative Nonfiction for our Massey Masters in Creative Writing, we decided that it'd work best if she concentrated on such "inward-looking" aspects of the genre as life writing and the personal essay, while I covered the "outward-looking" forms such as historiography and psychogeography - two of the most interesting areas of development over the past few decades.- Lectures: What is Psychogeography? (2018)

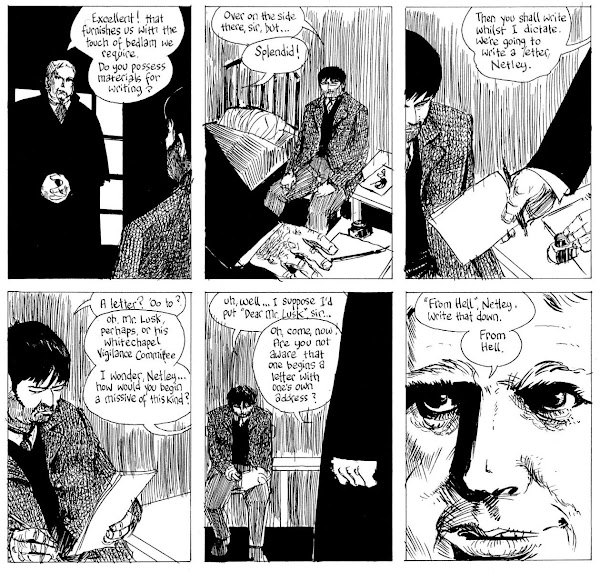

Among the readings I prescribed for our students was the chapter from the graphic novel From Hell where Alan Moore's pick for Jack the Ripper, Sir William Gull, Queen Victoria's royal physician, rides around London in a cab pointing out various mystic sites of Masonic significance, as "part of an elaborate mystical ritual to ensure male societal dominance over women."

It seemed to me as good an introduction as any to the underlying concepts of psychogeography. But what exactly is psychogeography? I wrote a few notes about it a few years ago in a blogpost about my decision to devote a new, standalone bookcase to the subject:

Not to find one’s way in a city may well be uninteresting and banal. It requires ignorance — nothing more. But to lose oneself in a city — as one loses oneself in a forest — that calls for a quite different schooling. Then, signboard and street names, passers-by, roofs, kiosks, or bars must speak to the wanderer like a cracking twig under his feet in the forest.- Walter Benjamin, A Berlin Chronicle (1932)

In many ways, psychogeography could be seen as a revival of French poet Charles Baudelaire's idea of the flâneur, the perambulating dandy, whose apparently aimless wanderings offer vital clues to the deeper meaning of modern urban environments.

Psychogeography continues to be associated principally with urban explorations - Peter Ackroyd's double-focus historical novel Hawksmoor (1985); Mike Davis's City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990); Alan Moore's graphic novel From Hell (1989-99), which postulates a Masonic "secret history" behind the Jack the Ripper murders; and Iain Sinclair's explorations of London's mythic past and present in such works as Lights out for the Territory: 9 Excursions in the Secret History of London (1997) - even Chris Trotter's chapter about an idealised dream Auckland in his alternative history of New Zealand No Left Turn (2007).

However, in his more recent book the Edge of the Orison (2005), Sinclair has extended his methodology to cover the rural haunts of nineteenth-century English nature poet John Clare, setting out to retrace the poet's famous 'Journey out of Essex' - Clare's own prose account of his 1841 escape from the asylum in which he had been incarcerated to find his lost love, Mary Joyce (unfortunately already three years dead).

Psychogeography, then, deals principally with boundary-crossings: whether those boundaries are those of genre (verse, fiction, non-fictional prose) or discipline (history, geography, travel, memoir and biography).

I suppose, in essence, that it consists of imposing a theory (generally of an occult or abstruse nature) on a landscape, more or less arbitrarily. The landscape is then interrogated to see whether or not it matches up with or confirms the theory, no matter how - intentionally - absurd it may be.

I don't know if I can really improve on that definition here, though of course a great deal more information on the subject can be accessed from the various links provided in the discussion above. What I'd prefer to do instead is to talk more about From Hell, the theories it contains, and its mercurial author Alan Moore.

As well as being one of England's most acclaimed graphic novelists and authors of comics - along with sundry other fictions - Moore is a self-proclaimed occultist and magician, as well as a passionate regionalist, deeply committed to his home-town Northampton and the surrounding Midlands region of Northamptonshire.

For From Hell, though, Moore shifted his vision to psychogeography's ground zero, the ancient and mysterious city of London, founded (as 'Londinium') by the Romans in the First Century CE, but undoubtedly far older than that - possibly (according to Wikipedia) as old as the fifth millennium BCE:

In 1993, remains of a Bronze Age bridge were found on the south foreshore upstream from Vauxhall Bridge. Two of the timbers were radiocarbon dated to 1750–1285 BC. In 2010, foundations of a large timber structure, dated to 4800–4500 BC, were found on the Thames's south foreshore downstream from Vauxhall Bridge.Where better, then, to set up his system of mystic correspondences?

As for their treatment of the murders themselves, Moore and Campbell are following in a lurid tradition of penny dreadful woodcuts and the sensationalist headlines in such publications as the Police News:

The "graphic" nature of the crimes is emphasised in pages such as the one below, where the women themselves are pictured passing around the daily paper:

This is certainly one reason I was glad to pick up a copy of Campbell's own Companion to this terrifyingly ambitious novel: described, not inappropriately, as the "Moby-Dick of Tabloid Murders" in Sam Thielman's 2021 review in The Daily Beast. Best to hear from the horse's mouth just what the two of them, Moore and Campbell, had in mind as they pored over their compendium of horrors and mystic lore.

Is the book a disappointment? Well, I guess that was to some extent inevitable, given that most of the questions I (for one) would like to ask about the novel are ones which no author can really answer. Are any of their conjectures actually true, for instance?

Was Sir William Gull an insane, cold-blooded murderer? Did whoever it was did the crimes chart his progress along Masonic lines, as would seem to be implied by that single word "Juwes" in the one piece of graffiti which appears to have been left by the Ripper himself?

The Juwes areIs "Juwes" a misspelling for "Jews", or - as various ingenious theorists insist - a reference to "Jubela, Jubelo and Jubelum, the three killers of Hiram Abiff, a semi-legendary figure in Freemasonry"?

The men that

Will not

be blamed

for nothing.

I guess I'm fortunate to have read the novel before watching the very disappointing film above: the first in a long line of poor cinematic adaptations of Moore's richest material.

For the rest, I can only continue to recommend Alan Moore as one of the genuinely indispensible English writers of the last forty years. His métier - the creation of multilayered universes powered by the clash of warring ideological and representational codes - may have been to some extent gazumped by cruder versions of the 'multiverse' hypothesis. But there's always a special twist of strangeness to an Alan Moore creation. His relentless intelligence guarantees his work life beyond its immediate cultural referents.

With that in mind, I've made a list below of his major works to date, in both the graphic novel and print fiction modes. His purely magical and performance pieces, though undoubtedly interesting to initiates, are a bit outside my bailiwick.

-

Comics:

- V for Vendetta (1982–1985 / 1988–1989)

- Marvelman / Miracleman (1982–1984)

- Swamp Thing (1984–1987)

- Watchmen (1986–1987)

- From Hell (1989–1998)

- Lost Girls (1991–1992 / 2006)

- Promethea (1999–2005)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999–2019)

- The Courtyard / Neonomicon / Providence (2003 / 2010 / 2015–2017)

- Miscellaneous (1982-2017)

- Poetry, Fiction & Non-fiction (1988-2024)

Texts:

Books I own are marked in bold:

The complex, stop-start way in which this novel was written and published piecemeal in different forms at different times is typical of Moore's earlier work for British comics journals. It's mainly for this reason (one presumes) that the classic Ballad of Halo Jones (1984-86) failed to reach the end of its projected arc.

- V for Vendetta. Illustrated by David Lloyd. 1982-83, 1988. New York: DC Comics, 1990.

V for Vendetta (1982-85), fortunately, was resurrected - and completed - by DC Comics in the United States in 1988–89 in a ten-issue colour limited series. This was subsequently collected as a trade paperback in 1990, and subsequently in a recoloured hardback edition in 2005.

The 2005 film adaptation, written by the Wachowskis and starring Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving in the principal roles, is actually one of the better cinematic versions of Moore's work. Nevertheless, he insisted on having his name removed from the titles, where it is described as being:

It's certainly true that the anarchist politics of the original novel have been largely muted in the film adaptation, some twenty years after its original publication, but it's worth noting that the Guy Fawkes-inspired "V" mask integral to the narrative has now become a bestseller, frequently used at political protests:Based on the graphic novel illustrated by David Lloyd

Anonymous, an online group associated with computer hacking, popularised the mask as a symbol for rebellion by wearing it at protests against governments. It prominently featured in the 2008 Project Chanology protests against the Church of Scientology. Moore described being pleased by the Fawkes mask's appearance at the protests ...

During the [2011-16] Occupy Wall Street and other Occupy protests, the mask appeared internationally as a symbol of popular revolution. Artist David Lloyd stated: "The Guy Fawkes mask has now become a common brand and a convenient placard to use in protest against tyranny — and I'm happy with people using it, it seems quite unique, an icon of popular culture being used this way."- Wikipedia: V for Vendetta - cultural impact

This is an even more vexed tale of publishing frustration:

- Miracleman, Book 1: A Dream of Flying. 1982-84. Illustrated by Garry Leach & Alan Davis. New York, Marvel, 2014.

- Miracleman, Book 2: The Red King Syndrome. 1985-89. Illustrated by Alan Davis & Chuck Beckham. New York, Marvel, 2014.

- Miracleman, Book 3: Olympus. Illustrated by John Totleben. 1985-89. New York, Marvel, 2015.

Originally created by Mick Anglo and published by L. Miller & Son, Ltd. as Marvelman between 1954 and 1963, the character was revived in 1982 for a revisionist story written by Alan Moore, beginning in the pages of British anthology Warrior. From 1985 the character was renamed Miracleman, and the series was continued by American publisher Eclipse Comics until 1993. Since 2009 the rights to the character have been licensed by Marvel Comics, who have published new material.- Wikipedia: Miracleman

The net result of all this chopping and changing of names and publishers was that the comic "Marvelman" created by Alan Moore was unavailable to fans until 2014.

Which is a shame, because it's a marvellously intricate story of superhero identity encased in a series of spheres of real and dreamed universes - themes which would be taken up more fully in his next grand project Watchmen.

Certainly it was these three comics Marvelman, Swamp Thing and Watchmen, all begun in the early to mid 1980s, which first established Moore as a master of narratives which expand on existing characters and storylines in a surprising and (at times) disconcerting way.

He couldn't simply be assigned to a title without wanting to reinvent it in his quest to discover the larger, archetypal meanings behind the existing machinery.

Perhaps the classic case of Moore's ability to revive - and deepen - a rather tired stock character is his work on the character "Swamp Thing", created by Len Wein and Berni Wrightson in 1972.

- Swamp Thing 1: Saga of the Swamp Thing. Illustrated by Stephen R. Bissette, John Totleben & Rick Veitch. 1983-84. New York: Vertigo, 1987.

- Swamp Thing 2: Love and Death. Illustrated by Stephen R. Bissette, John Totleben & Shawn McManus. 1971, 1984-85. New York: Vertigo, 1990.

- Swamp Thing 3: The Curse. Illustrated by Stephen R. Bissette & John Totleben. 1985. New York: Vertigo, 2000.

- Swamp Thing 4: A Murder of Crows. Illustrated by Stephen R. Bissette, John Totleben, Stan Woch, Rick Veitch, Ron Randall & Alfredo Alcalá. 1985-86. New York: Vertigo, 2001.

- Swamp Thing 5: Earth to Earth. Illustrated by Rick Veitch, John Totleben & Alfredo Alcalá. 1986-87. New York: Vertigo, 2002.

- Swamp Thing 6: Reunion. Illustrated by Tom Yeates, Rick Veitch, Stephen R. Bissette, Alfredo Alcalá & John Totleben. 1987. New York: Vertigo, 2003.

As Swamp Thing was heading for cancellation due to low sales, DC editorial agreed to give Alan Moore (at the time a relatively unknown writer in America whose previous work included several stories for 2000 AD, Warrior and Marvel UK) free rein to revamp the title and the character as he saw fit. Moore reconfigured the Swamp Thing's origin to make him a true monster as opposed to a human transformed into a monster. In his first issue, he swept aside the supporting cast Pasko had introduced in his year-and-a-half run as writer, and brought the Sunderland Corporation (a villainous group out to gain the secrets of Alec Holland's research) to the forefront, as they hunted down the Swamp Thing and "killed" him in a hail of bullets.This new Swamp Thing was not the actual character Alec Holland, but only believed itself to be so: "Holland had indeed died in the fire, and the swamp vegetation had absorbed his consciousness and memories and created a new sentient being that believed itself to be Alec Holland."- Wikpedia: Swamp Thing

Moore would later reveal, in an attempt to connect the original one-off "Swamp Thing" story from House of Secrets to the main Swamp Thing canon, that there had been dozens, perhaps hundreds, of Swamp Things since the dawn of humanity, and that all versions of the creature were designated defenders of the Parliament of Trees, an elemental community also known as "the Green" that connects all plant life on Earth.

You see what I mean? Rather than a series of banal superhero match-offs, Moore's immediate instinct was to enlarge the world of Swamp Thing to a cosmic level. He was now an eco-warrior who spoke for "the Green", a Gaia-like sentient consciousness connecting all living things on the planet.

What's more, this new conception of the character made it possible for him to move up and down the timeline of humanity, to match off with beings from other planetary ecologies, and generally strut his stuff on the largest stage imaginable.

Moore's Swamp Thing work remains very readable. The ways in which he was enlarging the comics genre as it was in the early 1980s can only really be compared to the early Dickens' transformation of early Victorian "comic cuts" serials into such masterpieces as Pickwick and Oliver Twist. Moore was a genius on that level, and he needed room to manoeuvre in.

That moment came with Watchmen, first serialised as a monthly comic in 1986-87 before being collected in a single volume at the end of 1987.

- Watchmen. Illustrated by Dave Gibbons. New York: DC Comics, 1987.

- Watchmen, dir. Zack Snyder, writ. David Hayter & Alex Tse (based on the graphic novel illustrated by Dave Gibbons) – with Malin Åkerman, Billy Crudup, Matthew Goode, Carla Gugino, Jackie Earle Haley, Jeffrey Dean Morgan & Patrick Wilson – (USA, 2009). 2-DVD set.

- Aperlo, Peter. Watchmen: The Film Companion. Titan Books. London: Titan Publishing Group Ltd., 2009.

1986 was, after all, the year of the great graphic novel explosion, and Watchmen was one of the three groundbreaking works which appeared at that time to confound dismissive critics (as chronicled in Douglas Wolk's 2007 book Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean).

They were (in alphabetical order):

- Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns (1986), a technically innovative four-issue comic book miniseries starring Batman, which is:

"widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Batman stories ever made, as well as one of the greatest works of comic art in general, and has been noted for helping reintroduce a darker and more mature-oriented version of the character (and superheroes in general) to pop culture during the 1980s."

- Alan Moore's Watchmen (1987), a comic book limited series by the British creative team of writer Alan Moore, artist Dave Gibbons and colorist John Higgins:

"Moore used the story as a means of reflecting contemporary anxieties, of deconstructing and satirizing the superhero concept and of making political commentary. Watchmen depicts an alternate history in which superheroes emerged in the 1940s and 1960s and their presence changed history so that the United States won the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal was never exposed."

- Art Spiegelman's Maus: A Survivor's Tale, Vol. 1 (1986). This novel first appeared, piecemeal, chapter by chapter, in Raw (1980-1991), the comics magazine he co-founded with his wife Françoise Mouly. The second (and final) volume was published in 1991:

"It depicts Spiegelman interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. The work employs postmodern techniques, and represents Jews as mice and other Germans and Poles as cats and pigs respectively. Critics have classified Maus as memoir, biography, history, fiction, autobiography, or a mix of genres. In 1992 it became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize."

This was - or at least should have been - the end of any idea that comics and graphic novels were a mere pulp genre, intended principally for children or the simple-minded: rather as crime stories had been regarded before the canonisation of such writers as Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

All three of these comics required sophisticated readers, alert to nuance, and (above all) interested in the cultural and political issues which stand front and centre in these complex works.

It's important to emphasise here that the film of Watchmen (in its various versions) is more illustrator Dave Gibbons' gig than Alan Moore's. Director Zack Snyder was forced to leave out one of the graphic novel's crucial subplots - although an animated version of this, a pirate story, was later released separately.

Watchmen, in both film and novel form, is indeed a critique of superhero comics - rather as Don Quixote is 'just' a critique of chivalric romances - but that's only one of the many things it does.

Moore's inventiveness defies simple description. His idea that in a parallel world where superheroes are commonplace Pirate Comics might take over the place of Superman and Batman in popular culture evolves into a profound meditation on the nature of violence, and - in particular - our obsession with repetitive reresentations of it, whether it be in the form of slasher movies or blood-soaked whodunits.

It's a major work by a major writer. It's probably his masterpiece, his single most accomplished comic, but as you'll have gathered from the other entries here, there's stiff competition for that place.

From Hell was, I suppose, the beginning of Moore's career as a consciously independent comics auteur rather than a somewhat rebellious hireling of the great warring companies. You can find more on its (rather complex) publishing history here, but the point is that Eddie Campbell was already better known as the author of the autobiographical comic Alec than as an illustrator of other people's work.

- From Hell: Being a Melodrama in Sixteen Parts. Illustrated by Eddie Campbell. 1999. Top Shelf Productions. San Diego, CA: IDW Publishing, 2019.

- From Hell: Being a Melodrama in Sixteen Parts. Illustrated by Eddie Campbell. 1999. Sydney: Bantam Books, 2001.

- [with Eddie Campbell] The From Hell Companion. Foreword by Charles Hatfield & Craig Fischer. Marietta, GA: Top Shelf Productions / London: Knockabout Comics, 2013.

He was therefore far more of an equal partner in this whole decade-long enterprise than Moore's previous artist collaborators.

I've already said a certain amount above about the particular Jack the Ripper theory espoused by this vast - and rather monstrous - piece of work. Its innovations go far beyond that, though. It's certainly a crucial addition to the 'secret history of London' genre popular in our fin-de-siècle, but also a major piece of self-reflexive, deconstructionist narrative in its own right.

As I said in an earlier post called Carrolliana, detailing some of the stranger aspects of the cultural half-life of Lewis Carroll's creations:

- Moore, Alan. Lost Girls. Illustrated by Melinda Gebbie. 3 vols. Marietta, Georgia: Top Shelf Productions, 2006.

To continue with the theme of graphic novels, Lewis Carroll's favourite muse, Alice Pleasance Hargreaves (née Liddell), also makes an extended appearance in Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie's weird semi-pornographic extravaganza Lost Girls, alongside Dorothy Gale from L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), and Wendy Darling from J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan (1904).Moore's own comments on his and Melinda Gebbie's motives for writing the work should also be put on record here:

As Wikipedia puts it, in its characteristically po-faced fashion:They meet as adults in 1913 and describe and share some of their erotic adventures with each other.The book culminates with the eruption of the First World War in 1914. Here's a medley of the original covers for the 3-volume slipcase edition to give you the general idea:

Like all of Alan Moore's books, this one is both intricately plotted and technically ingenious. Beyond that, though, it's hard to see as much substance in it as in Talbot's almost exactly contemporaneous non-fiction novel Alice in Sunderland (2007).

Certainly it seemed to us that sex, as a genre, was woefully under-represented in literature. Every other field of human experience — even rarefied ones like detective, spaceman or cowboy — have got whole genres dedicated to them. Whereas the only genre in which sex can be discussed is a disreputable, seamy, under-the-counter genre with absolutely no standards: [the pornography industry] — which is a kind of Bollywood for hip, sleazy ugliness.- Wikipedia: Lost Girls: Literary Themes

Around the turn of the millennium, Alan Moore and his collaborators launched a stunning new enterprise: America's Best Comics. While storylines by other writers and artists were included in each issue, it mainly served as a vehicle for four major serials by Moore himself:

- America’s Best Comics. No. 1. (2000)

- Promethea: Book 1, issues #1-6 (2000)

- Promethea. Illustrated by J. H. Williams III & Mick Gray. Collected Edition Book 1. Issues #1-6. 1999-2000. La Jolla, CA: America’s Best Comics, 2000.

- Promethea: Book 2, issues #7-12 (2001)

- Promethea: Book 3, issues #13-18 (2002)

- Promethea: Book 4, issues #19-25 (2003)

- Promethea: Book 5, issues #26-32 (2004)

"The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a strip which merged several famous Victorian era fiction characters into one world; Tom Strong, an homage to pulp fiction heroes such as Tarzan and Doc Savage; Top 10, a police procedural set in a police precinct in a city where everyone has superpowers or is a costumed adventurer; and Promethea, one of Moore's most personal pieces which detailed his view on magic."The enterprise folded sometime in 2005, though various offshoots continued as late as 2010. I'm very grateful now to the friend who bought me a copy of issue #1. I didn't follow up on this promising beginning, but I have come to admire greatly at least some of the work Moore contributed to this comic.

Promethea, for instance, should be regarded as one of his major works. The intricate, fabular complexities of internested worlds of reality and legend can surely not be taken much further than he does here - without losing all possibility of coherence, that is.

The art is also marvellously bright and clear. Though I haven't yet acquired a full run of the title, I have read almost all of it at one time or another. It's probably the major lacuna for me in this list of my collection of Mooreana to date.

•

Alan Moore & Kevin O'Neill: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Omnibus (2019)

Alan Moore & Kevin O'Neill: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Omnibus (2019)

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

(1999-2019)

(1999-2019)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, vol. I: issues #1-6 (2000)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Illustrated by Kevin O'Neill. Vol. 1. La Jolla, CA: America’s Best Comics, 2000.

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, vol. II: issues #1-6 (2003)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Illustrated by Kevin O'Neill. Vol. 2. La Jolla, CA: America’s Best Comics, 2003.

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Black Dossier (2007)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, vol. III: Century (2009-12)

- Century 1910

- Century 1969

- Century 2009

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Nemo Trilogy (2013-15)

- Nemo: Heart of Ice

- Nemo: The Roses of Berlin

- Nemo: River of Ghosts

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, vol. IV: Tempest (2018-19)

"What do they know of England, who only England know?" Or perhaps one might paraphrase Kipling's much-quoted verse into "What do they know of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen who only the truly dreadful feature film know?

Even the line-ups are rather dissimilar. Here's the core cast of the graphic novel:

The movie, by contrast, takes the concept of using characters from existing fictions to rather absurd lengths. We still have Sean Connery as Allan Quatermain, Naseeruddin Shah as Nemo, Peta Wilson as Mina Harker, and Jason Flemyng as Dr. Henry Jekyll / Edward Hyde. But was there any need to add Dorian Gray, Tom Sawyer, and Moby-Dick's Ishmael to the list of principals?

- Mina Murray (from Dracula)

- Allan Quatermain (from King Solomon's Mines)

- Captain Nemo (from Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea)

- Dr. Henry Jekyll / Edward Hyde (from Robert Louis Stevenson's novella)

- Hawley Griffin (from The Invisible Man)

- Orlando / Roland (from Virginia Woolf's novel)

- Thomas Carnacki (from William Hope Hodgson's stories)

- A. J. Raffles (from E. W. Hornung's stories)

Since then, of course, the British TV series Penny Dreadful (2014-16) has used the same idea - and some of the same characters - to rather better effect.

The comic itself, however, remains great fun to read and annotate. Its run is now, however - or so we've been told - definitively concluded:

The fourth volume was released in six parts, starting in June 2018. Not only has it been announced as the last League story, but also creators Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill have described it as their final work in the comic book medium. The plot is described as follows: "Opening simultaneously in the panic-stricken headquarters of British Military Intelligence, the fabled Ayesha's lost African city of Kor and the domed citadel of ‘We’ on the devastated Earth of the year 2996, the dense and yet furiously-paced narrative hurtles like an express locomotive across the fictional globe from Lincoln Island to modern America to the Blazing World; from the Jacobean antiquity of Prospero's Men to the superhero-inundated pastures of the present to the unimaginable reaches of a shimmering science-fiction future. With a cast-list that includes many of the most iconic figures from literature and pop culture, and a tempo that conveys the terrible momentum of inevitable events, this is literally and literarily the story to end all stories".- Wikipedia: List of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen titles

•

Jasen Burrows: Providence 3 Cover (2015)

The Courtyard / Neonomicon / Providence

(2003 / 2010 / 2015-17)

(2003 / 2010 / 2015-17)

In one of my pieces on the sage of Providence, Rhode Island, the legendary H. P. Lovecraft, I wrote as follows about the various offshoots of Moore's stand-alone comic The Courtyard (now collected with its sequel Neonomicon in a single volume):

- Neonomicon Collected. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2011.

- Providence: Act 1. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Issues #1-#4. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2017.

- Providence: Act 2. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Issues #5-#8. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2017.

- Providence: Act 3. Illustrated by Jacen Burrows. Issues #9-#12. Rantoul, Illinois: Avatar Press, 2017.

One of the most pleasing of the recent tributes to his influence is Alan Moore's remarkable series of comics set in a slightly alternative America of the 1930s:

Composed in his characteristic cross-genre mix of 'straight' comics and associated prose pieces and appendices, Moore's narrative describes the odyssey of a hapless journalist over a thinly disguised version of Lovecraft's New England, resulting in the usual dire consequences for the entire human race.

Let's just say that these comics go some places that other fan fictions seldom do. They take a good look at Lovecraft's xenophobia and misognyny but pay full tribute to the power of his mythopoeic imagination, also. Not always to comforting effect, it should be said.

What else can one say? Unlike Matt Ruff's misleadingly titled novel Lovecraft County, now adapted by HBO into a TV series, Moore understands Lovecraft's world thoroughly.

In an analysis of the series, Maya Phillips of The New York Times criticized it for "exploiting [the past] for the purposes of its convoluted fiction", despite a promising premise. She accused the show's creators of using historical events purely "to get points for relevance", notable examples of this being the funeral of Emmett Till and the Tulsa race massacre, both of which are featured in the show.The same could not be said of Moore's comic. On the contrary, in fact. There's little that's "convoluted" here, but rather an aching simplicity in his portrayal of a world as much under threat by Lovecraft's racist and miogynist convictions beliefs as it is by his fabled "Elder Gods."

It's difficult to compile a comprehensive list of Alan Moore's published work in comics. Wikipedia's "Alan Moore Bibliography" gives all the detail that most of us could desire, but here's a chronological ordering of his major series and graphic novels, complete or incomplete:

- Moore, Alan. DC Universe: The Stories of Alan Moore. New York: DC Comics, 2006.

- [Superman:] "For the Man Who Has Everything". Artist: Dave Gibbons (1985)

- [Detective Comics:] "Night Olympics". Artist: Klaus Janson (April–May 1985)

- [Green Lantern:] "Mogo Doesn't Socialize". Artist: Dave Gibbons (May 1985)

- [Vigilante:] "Father's Day". Artist: Jim Baikie (May–June 1985)

- [The Omega Men:] "Brief Lives". Artist: Kevin O'Neill (May 1985)

- [The Omega Men:] "A Man's World". Artists: Paris Cullins & Rick Magyar (June 1985)

- [DC Comics Presents:] "The Jungle Line". Artists: Rick Veitch & Al Williamson (September 1985)

- [Green Lantern:] "Tygers". Artist: Kevin O'Neill (1986)

- [Superman:] "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?". Artists: Curt Swan, George Pérez & Kurt Schaffenberger (September 1986)

- [Secret Origins:] "Footsteps". Artist: Joe Orlando (January 1987)

- [Batman:] "Mortal Clay". Artist: George Freeman (July 1987)

- [Green Lantern:] "In Blackest Night". Artists: Bill Willingham & Terry Austin (August 1987)

- [Batman:] "The Killing Joke". Artist: Brian Bolland (1988)

Titles I own are marked in bold:

- V for Vendetta (1982–1985 / 1988–1989)

- Marvelman / Miracleman (1982–1984)

- Skizz (1983–1985)

- The Ballad of Halo Jones (1984–1986)

- Swamp Thing (1984–1987)

- Watchmen (1986–1987)

- Batman: The Killing Joke (1988)

- From Hell (1989–1996)

- Big Numbers (1990)

- A Small Killing (1991)

- Lost Girls (1991–1992 / 2006)

- Top 10 (1999–2001)

- Promethea (1999–2005)

- Tom Strong (1999–2006)

- The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (1999–2019)

- A Disease of Language (1999-2001)

- The Courtyard (2003)

- Neonomicon (2010)

- Fashion Beast (2012–2013)

- Providence (2015–2017)

...

- A Disease of Language. Illustrated by Eddie Campbell. 1999 & 2001. London: Knockabout – Palmano Bennett, 2005.

When I was trying to suggest parallels for Bill Direen's innovative NZSF novel Song of the Brakeman (2006) in a blogpost, this is one of the few that came to mind:

- Voice of the Fire: A Novel. 1996. Illustrated by José Villarubia. Introduction by Neil Gaiman. Atlanta & Portland: Top Shelf Productions, Inc., 2003.

My final exhibit is comics-supremo Alan Moore's debut print - as opposed to graphic - novel, Voice of the Fire. The resemblances here with Riddley Walker are strong, despite the prehistoric setting of the first section of his story. This makes it what? Fantasy? Historical fiction? Fantasy-&-SF? In the end, all one can really call it is a singularly ambitious novel, tout court.I haven't yet gone much further than that into Alan Moore's new realm of print fiction, though I certainly hope to sometime in the near future. It was twenty years before he published another novel, Jerusalem (2016), but since then there's been a collection of short stories, and - now - the first volume in his new "Long London Quintet" is about to appear from Bloomsbury Publishing.

I've supplied, below, a list of all his works in this mode which I'm aware of at present. No doubt it will have to be expanded on a fairly regular basis as he continues to produce new work:

Titles I own are marked in bold:

- The Mirror of Love (1988)

- Voice of the Fire (1996)

- Alan Moore's Writing for Comics (2003)

- Jerusalem (2016)

- Illuminations (2022)

- [with Steve Moore] The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic (2024)

- The Long When. The Long London Quintet, 1 (2024)

•

- category - Comics & Graphic Novels: Cartoons & Graphic Novels (English)