William Dunbar: Lament for the Makars (c.1505)

William Dunbar: Lament for the Makars (c.1505)[Pieter Bruegel the Elder: 'The Triumph of Death' (c.1562)]

•

Alexander Moffat: Poets' Pub

Alexander Moffat: Poets' Pub[l-to-r: Norman MacCaig, Hugh MacDiarmid, Sorley Maclean, Iain Crichton Smith,

George Mackay Brown, Sydney Goodsir Smith, Edwin Morgan, Robert Garioch]

[Bookcase reorganisation: February 12-14, 2022]:

I that in heill wes and gladnes,A long overdue reorganisation of the bookcases at our house has given me the opportunity to group all my Scottish books in one place, which in its turn has reminded me of just how many brilliant writers hail from there.

Am trublit now with gret seiknes,

And feblit with infermite;

Timor mortis conturbat me.

Our plesance heir is all vane glory,

This fals warld is bot transitory,

The flesche is brukle, the Fend is sle;

Timor mortis conturbat me.[I who was in health and gladness,

Am troubled now with great sickness,

And feebled with infirmity;

The fear of death devours me.

Our pleasure here is all vainglory,

This false world is but transitory,

The flesh is mighty, the Fiend is sly;

The fear of death devours me.]

There are far too many for convenient listing, in fact, so I decided instead to make a rollcall of my particular favourites among the Scottish poets: those whom Dunbar, in his famous lament quoted above, calls the 'makars' [makers].

Most people would probably begin their lists with Robert Burns, but I'd prefer to start a bit further back, with the extraordinary galaxy of fifteenth century poetic talent generally grouped under the label 'The Scottish Chaucerians.' Chaucer was certainly a strong influence on them, but then so were many other classical and European poets. The only real justification for the name is a strong common interest in storytelling in the vernacular.

I se that makaris amang the laifIn any case, here's my very partial list of some of the Scottish poets who particularly appeal to me, either for aesthetic or personal reasons:

Playis heir ther pageant, syne gois to graif;

Sparit is nocht ther faculte;

Timor mortis conturbat me.

He hes done petuously devour,

The noble Chaucer, of makaris flour,

The Monk of Bery, and Gower, all thre;

Timor mortis conturbat me.[I see that makers among the rest

Play here their pageant, then go to grief,

Their faculty is not exempt;

The fear of death devours me.

He has most pitilessly devoured

The noble Chaucer, of makers flower,

The monk of Bury [= John Lydgate], and Gower, all three;

The fear of death devours me.]

I have to say that this list has cost me some soul-searching. What about William Dunbar himself? What about Allan Ramsay, or James Thomson? Or, moving to more modern times, Iain Crichton-Smith? Kathleen Jamie? Liz Lochead? Norman MacCaig? Edwin Morgan? These are all fine and influential poets, but not so close to me as the ones listed above.

- George Mackay Brown (1921-1996)

- Robert Burns (1759-1796)

- Douglas Dunn (1942- )

- W. S. Graham (1918-1986)

- Robert Henryson (1425-1506)

- Sir David Lyndsay (1490-1555)

- Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978)

- William McGonagall (1825-1902)

- Sorley MacLean (1911-1996)

- James Macpherson (1736-1796)

- Edwin Muir (1887-1959)

- Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832)

- Andrew Young (1885-1971)

James Hogg and Robert Louis Stevenson - both brilliant poets - I left out because it's primarily their artistry in prose that speaks to me. Some might jib at the inclusion of Sir Walter Scott for much the same reason, but in that case it was an early reading of The Lay of the Last Minstrel which was really decisive.

Here they are again, this time arranged chronologically, as I've decided to do below as well:

Interestingly enough, the only one included in Dunbar's own long list of contemporary makers is Robert Henryson:

- Robert Henryson (1425-1506)

- Sir David Lyndsay (1490-1555)

- James Macpherson (1736-1796)

- Robert Burns (1759-1796)

- Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832)

- William McGonagall (1825-1902)

- Andrew Young (1885-1971)

- Edwin Muir (1887-1959)

- Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978)

- Sorley MacLean (1911-1996)

- W. S. Graham (1918-1986)

- George Mackay Brown (1921-1996)

- Douglas Dunn (1942- )

In Dumfermelyne he hes done rouneNo-one knows much about 'Sir John the Ross'. The wikipedia article on the poem is largely unforthcoming: 'no known works; he was Dunbar's commissar in "The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy".' I suppose it's comforting to know that one of my distant ancestors was celebrated enough to included in such a danse macabre of plague victims.

With Maister Robert Henrisoun;

Schir Johne the Ros enbrast hes he;

Timor mortis conturbat me.[He's held converse in Dumferline

With Master Robert Henryson,

Sir John the Ross embraced has he;

The fear of death devours me.]

Which is, I suppose, a large part of the point of all this. I lived in Scotland for four years in the late 1980s, and had a hard reckoning with my own Scottish heritage then. It remains important to me, but I was forced to acknowledge that any illusions I had about actually being 'Scottish' were largely sentimental and unreal.

While my paternal grandmother was a native Gaelic speaker from the West Coast of the Highlands, and my grandfather a Scots-speaking native of Dingwall in Easter Ross (now known as 'Ross and Cromarty'), I am myself, ineradicably and irredeemably, a Pākehā New Zealander.

So while I will continue to love Scottish culture and literature, and to feel a special affinity for certain parts of the country with strong family associations: Polbain and Achiltibuie on the West Coast above Ullapool, Dingwall itself, it's really my four years in Edinburgh which have left me with a particular affection for that grand and, yes, at times, cruel city.

My grandmother, who studied at Glasgow University before the First World War, used to refer to Scotland's capital as 'East-windy and West-endy'. The winds are still there, certainly, as are some of the social pretensions, but there's a realler city underneath all that which begins to manifest slowly after your first couple of nine-month-long winters.

As usual, Dunbar puts it all in perspective:

Sen he hes all my brether tane,

He will nocht lat me lif alane,

On forse I man his nyxt pray be;

Timor mortis conturbat me.

Sen for the deid remeid is none,

Best is that we for dede dispone,

Eftir our deid that lif may we;

Timor mortis conturbat me.[Since he has all my brothers taken,

He will not let me survive alone,

I fear I must his next prey be;

The fear of death devours me.

Since for the dead there's no remedy,

It's best for death we be ready,

So after death we may live on;

The fear of death devours me.]

- Robert Henryson

(c.1425-1506)

Starting with Robert Henryson does make a certain sense. He is, in many ways, both the most original and the most appealing of the fifteenth century Scottish poets.

He's celebrated for the psychological insight of his Testament of Cresseid - a kind of sequel to Chaucer's epic Troilus and Crisyede. Where Chaucer concentrates on the problems faced by Troilus, Henryson pleads the point of view of his allegedly 'faithless' lover Cressida.

Probably his most attractive works for modern readers, however, are his versions of Aesop's Fables. As you can see from the short extract I've provided below from the most famous of these, the fable of the town-mouse and the country-mouse, Henryson includes a host of contemporary details in his accounts of the two mice.

The town mouse, for instance, was a 'guild brother' and a 'free burgess', who was exempt from 'tolls' in her wanderings through nearby chests and pantries. Her younger sister in the country, by contrast, lived 'as outlaws do' on the lone wastes 'under bush and briar.'

When the town mouse decides to pay a visit to her sister, she takes a 'pikestaff in her hand / like a pure pilgrim', and sets forth on the open road. What's most irresistible, though, is her heartfelt call to her longlost sibling:“Cum furth to me, my awin sweit sister deir,

'Cry peep once!' It's this strange blend of mouse and human traits which is so supremely pleasing, and which makes this such an incomparable piece of writing. Henryson is of human, not merely academic, interest as a poet, and well repays the trouble of mastering the curious spelling and few dialect terms needed to understand his verse.

Cry peip anis!”

from The Taill of the Uponlandis Mous and the Burges Mous Esope myne authour makis mentioun Of twa myis and thay wer sisteris deir Of quham the eldest in ane borous toun, The yungir wynnit uponland weill neir Richt soliter, quhyle under busk and breir, Quhilis in the corne in uther mennis skaith As owtlawis dois and levit on hir waith. This rurall mous into the wynter tyde Had hunger, cauld, and tholit grit distres. The tother mous that in the burgh couth byde, Was gild brother and made ane fre burges, Toll-fre alswa but custum mair or les And fredome had to ga quhairever scho list Amang the cheis and meill in ark and kist. Ane tyme quhen scho wes full and unfutesair, Scho tuke in mynd hir sister uponland And langit for to heir of hir weilfair To se quhat lyfe scho led under the wand. Bairfute, allone, with pykestaf in hir hand As pure pylgryme scho passit owt off town To seik hir sister baith oure daill and down. Throw mony wilsum wayis can scho walk, Throw mure and mosse, throw bankis, busk, and breir, Fra fur to fur, cryand fra balk to balk, “Cum furth to me, my awin sweit sister deir, Cry peip anis!” With that the mous couth heir And knew hir voce as kinnismen will do Be verray kynd and furth scho come hir to. The hartlie cheir, lord God geve ye had sene Beis kythit quhen thir sisteris twa war met, Quhilk that oft syis wes schawin thame betwene! For quhylis thay leuch and quhylis for joy thay gret, Quhyle kissit sweit and quhilis in armis plet And thus thay fure quhill soberit wes their mude, Syne fute for fute unto the chalmer yude. ...

-

Poetry:

- The Poems and Fables of Robert Henryson, Schoolmaster of Dunfermline. Ed. H. Harvey Wood. 1933. 2nd ed. 1958. Edinburgh & London: Oliver & Boyd / New York: Barnes & Noble, 1968.

•

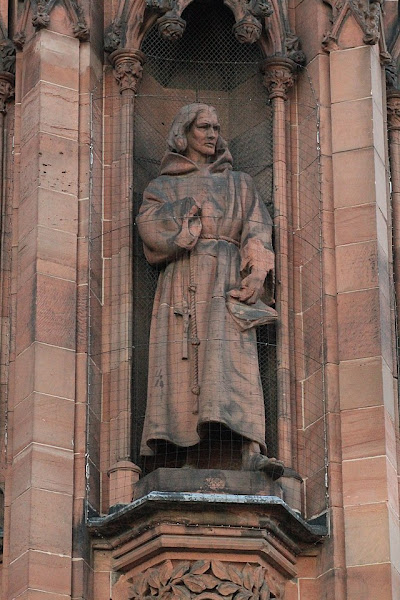

Sir David Lyndsay (1425-1506)

Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount

(c.1490-1555)

Henryson is a poet I first encountered while studying Old and Middle English at university. I had a dream at the time of becoming a Medieval specialist, but that soon faded as I discovered an inability to close off new areas of interest as they rose up in me. This 'Beowulf to Virginia Woolf' tendency drove me, eventually, into the broad church of writing studies.

As an example of this, my interest in Sir David Lyndsay comes mainly from the fact that C. S. Lewis quotes two lines from his poem 'Ane Dialog' at the beginning of his fantasy novel That Hideous Strength:The shadow of that hideous strength

This - embedded in a lengthy description of the Tower of Babel - I found irresistible: trenchantly phrased, and yet with that slight air of weirdness which comes from older English idiomatic writing.

Sax mile and mair it is of length

I was fortunate enough to find an old copy of Lyndsay's Collected Poems in a local second-hand shop, and did my best to work my way through his mad play Ane Satire of the Threi Estates - which was successfully revived for the Edinburgh Festival back in 1948, and numerous times since, if only I'd known it.

He lacks the human appeal of Henryson, it must be said, but his sinewy verse retains a flavour of the Scottish vernacular despite the five centuries between us and him.

from Ane Dialog betuix Experience and ane Courteour THEIR great fortress then did they found, And cast till they gat sure ground. All fell to work, both man and child, Some howkit clay, some burnt the tyld. Nimrod, that curious champion, Deviser was of that dungeon. Nathing they spared their labors, Like busy bees upon the flowers, Or emmets travelling into June; Some under wrocht, and some aboon, With strang ingenious masonry, Upward their wark did fortify; The land about was fair and plain, And it rase like ane heich montane. Those fulish people did intend, That till the heaven it should ascend; Sae great ane strength was never seen Into the warld with men’s een. The wallis of that wark they made, Twa and fifty fathom braid: Ane fathom then, as some men says, Micht been twa fathom in our days; Ane man was then of mair stature Nor twa be now, of this be sure. The translator of Orosius Intil his chronicle writes thus; That when the sun is at the hicht, At noon, when it doth shine maist bricht, The shadow of that hideous strength Sax mile and mair it is of length: Thus may ye judge into your thocht, Gif Babylon be heich or nocht. Then the great God omnipotent, To whom all things been present, He seeand the ambition, And the prideful presumption, How thir proud people did pretend, Up through the heavens till ascend, Sic languages on them he laid, That nane wist what ane other said; Where was but ane language afore, God send them languages three score; Afore that time all spak Hebrew, Then some began for to speak Grew, Some Dutch, some language Saracen, And some began to speak Latin. The maister men gan to ga wild, Cryand for trees, they brocht them tyld. Some said, Bring mortar here at ance, Then brocht they to them stocks and stanes; And Nimrod, their great champion, Ran ragand like ane wild lion, Menacing them with words rude, But never ane word they understood.

-

Poetry:

- Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount, Lyon King of Arms. The Poetical Works: A New Edition Carefully Revised. 2 vols. Early Scottish Poets. Edinburgh: William Paterson, 1871.

•

George Romney: James Macpherson (1779-80)

James Macpherson

(1736-1796)

James Macpherson is often treated as an exploded hoaxer rather than a poet in his own right. And yet, in his day, he was one of the most widely read writers in Europe. Napoleon, in particular, is said to have carried a French translation of Ossian with him on all his campaigns.

It's true that the corpus of Ossianic poems were originally presented by Macpherson as direct translations from Gaelic originals composed by Ossian himself, son of the mythical Irish hero Finn MacCool. This is clearly not so, and elaborate attempts to refute Macpherson's claims dominated discussions of the poems from the late eighteenth century onwards.

Macpherson was a competent Gaelic speaker, and had certainly collected a number of traditional ballads about Finn and the Fianna in his wanderings around the Highlands. He 'translated' these into a mock-heroic idiom borrowed from contemporary versions of Homer and other Classical epic poets, and certainly some obfuscation was involved in this transformation.

The powerful effect of these poems on readers, though, came from their anticipation of the themes of Romantic poets such as Byron and Coleridge long before they had themselves set pen to paper. It's no exaggeration to say that Ossian helped create the Romantic sensibility which would, eventually, supersede it.

Fortunately the poems were reprinted a few years ago by Edinburgh University Press, but before that they were quite difficult to obtain. They should constitute a source of pride rather than slightly bashful embarrassment for contemporary Scots, however. They certainly continue to fascinate me, and I can't resist adding new editions to my collection whenever I see them.

from Fingal: An Ancient Epic Poem in Six Books

Cuthullin sat by Tura's wall: by the tree of the rustling sound. His spear leaned against a rock. His shield lay on grass by his side. Amid his thoughts of mighty Carbar, a hero slain by the chief in war; the scout of ocean comes, Moran the son of Fithil!

"Arise," says the youth, "Cuthullin, arise. I see the ships of the north! Many, chief of men, are the foe. Many the heroes of the sea-borne Swaran!" "Moran!" replied the blue-eyed chief, "thou ever tremblest, son of Fithil! Thy fears have increased the foe. It is Fingal, king of deserts, with aid to green Erin of streams." "I beheld their chief," says Moran, "tall as a glittering rock. His spear is a blasted pine. His shield the rising moon! He sat on the shore! like a cloud of mist on the silent hill! Many, chief of heroes! I said, many are our hands of war. Well art thou named, the Mighty Man; but many mighty men are seen from Tura's windy walls."

"He spoke, like a wave on a rock, who in this land appears like me? Heroes stand not in my presence: they fall to earth from my hand. Who can meet Swaran in fight? Who but Fingal, king of Selma of storms? Once we wrestled on Malmor; our heels overturned the woods. Rocks fell from their place; rivulets, changing their course, fled murmuring from our side. Three days we renewed the strife; heroes stood at a distance and trembled. On the fourth, Fingal says, that the king of the ocean fell! but Swaran says, he stood! Let dark Cuthullin yield to him, that is strong as the storms of his land!" ...

-

Poetry:

- The Poems of Ossian, with Dissertations on the Era and Poems of Ossian; and Dr. Blair’s Critical Dissertation. Edinburgh: John Grant, 1894.

- The Poems of Ossian. Ed. William Sharp. Edinburgh: John Grant, 1926.

- Poems of Ossian: A Facsimile of the 1805 Edition. Introduction by John MacQueen. 2 vols. Edinburgh: James Thin / The Mercat Press, 1971.

- The Poems of Ossian, and Related Works. Ed. Howard Gaskill. Introduction by Fiona Stafford. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996.

•

Alexander Nasmyth: Robert Burns (1828)

Robert Burns

(1759-1796)

I'm afraid that Robert Burns remains a poet more praised than read - and praised generally for patriotic rather than artistic reasons. Which is a real shame, as his fame among his contemporaries was no chimera, but was solidly based on the revolutionary nature of his talent.

Rather than seeing him as the first in a long line of peasant poets - John Clare, W. H. Davies, and P. J. Kavanagh among them - it's probably better to consider him as a proto-romantic. Certainly that's the way Wordsworth and Keats regarded him.

Nor is the language really much of an obstacle. 'Tam O'Shanter' and his other famous works may look a bit daunting at first, but can be easily followed with the help of a few marginal notes.

So forget all that stuff about Burns Day, haggis, and the 'chieftain of the pudding race.' Burns may have had a lively sense of humour, but he was no clown. He may have got drunk on occasion, but the temptations were many in his few months of fame in Edinburgh society. The real obstacle to reading Burns is the sheer bulk of his collected work.

Once you've sampled the acknowledged gems, though, you'll want to continue reading him anyway.

A Man’s a Man for A’ That Is there, for honest poverty, That hings his head, an’ a’ that? The coward slave, we pass him by, We dare be poor for a’ that! For a’ that, an’ a’ that, Our toils obscure, an’ a’ that; The rank is but the guinea’s stamp; The man’s the gowd for a’ that, What tho’ on hamely fare we dine, Wear hoddin-gray, an’ a’ that; Gie fools their silks, and knaves their wine, A man’s a man for a’ that. For a’ that, an’ a’ that, Their tinsel show an’ a’ that; The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor, Is king o’ men for a’ that. Ye see yon birkie, ca’d a lord Wha struts, an’ stares, an’ a’ that; Tho’ hundreds worship at his word, He’s but a coof for a’ that: For a’ that, an’ a’ that, His riband, star, an’ a’ that, The man o’ independent mind, He looks and laughs at a’ that. A prince can mak a belted knight, A marquis, duke, an’ a’ that; But an honest man’s aboon his might, Guid faith he mauna fa’ that! For a’ that, an’ a’ that, Their dignities, an’ a’ that, The pith o’ sense, an’ pride o’ worth, Are higher rank than a’ that. Then let us pray that come it may, As come it will for a’ that, That sense and worth, o’er a’ the earth, May bear the gree, an’ a’ that. For a’ that, an’ a’ that, It’s coming yet, for a’ that, That man to man, the warld o’er, Shall brothers be for a’ that.

-

Poetry:

- Burns, Robert. Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. 1786. Poetry First Editions. Note on the Text by Michael Schmidt. London: Penguin, 1999.

- Smith, Alexander, ed. Poems, Songs and Letters: Being The Complete Works of Robert Burns, Edited from the Best Printed and Manuscript Authorities with Glossarial Index and a Biographical Memoir. The Globe Edition. London: Macmillan and Co., 1868.

- Burns, Robert. The Canongate Burns: The Complete Poems and Songs. Ed. Andrew Noble & Patrick Scott Hogg. Canongate Classics, 104. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2001.

- Burns, Robert. Selected Letters. Ed. J. DeLancey Ferguson. The World’s Classics. London: Geoffrey Cumberlege / Oxford University Press, 1953.

- Burns, Robert. The Merry Muses of Caledonia. Ed. James Barke & Sydney Goodsir Smith. Preface by J. DeLancey Ferguson. 1965. London: Panther Books, 1970.

Prose:

Edited:

•

Sir Henry Raeburn: Sir Walter Scott (1822)

Sir Walter Scott

(1771-1832)

Is Sir Walter Scott a good poet? I myself would call him one of the best narrative poets in the English language. Is he a great poet? Well, it depends what you mean by that.

His verse may lack the complexity and depth of such contemporaries such as Wordsworth and Byron, but then he had rather different aims. In any case, Scott's world renown depends mainly on his invention of an entirely new genre: the historical novel.

For sheer entertainment value, though, it's hard to beat that string of wonderful book-length poems with which he opened his career: The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805), Marmion (1808), The Lady of the Lake (1810), The Lord of the Isles (1815), and numerous others.

Nor is his collection of ballads, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802-3) an inconsiderable achievement. It may lack the scholarly rigour which came to dominate the field of folklore studies later in the nineteenth century, but it was the popularity of collections such as Scott's and Bishop Percy's Reliques of Ancient Poetry (1765) which provided the impetus for further work in the field.

After all, Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm were still schoolboys when Scott published his collection of ballads, and it helped to inspire the first considerable German work in the field, Arnim and Brentano's Des Knaben Wunderhorn: Alte deutsche Lieder [The Boy's Magic Horn: Old German Songs] (1805-8).

Depending on your politics, Scott himself can seem like a wise, long-suffering old man or a horrible, hypocritical, class-conscious Tory. Best to leave such assumptions aside, I would argue, and surrender to the sheer narrative (and emotional) momentum of his work.

Proud Maisie Proud Maisie is in the wood, Walking so early; Sweet Robin sits on the bush, Singing so rarely. "Tell me, thou bonny bird, When shall I marry me?"— "When six braw gentlemen Kirkward shall carry ye." "Who makes the bridal bed, Birdie, say truly?"— "The gray-headed sexton That delves the grave duly. "The glowworm o'er grave and stone Shall light thee steady; The owl from the steeple sing, 'Welcome, proud lady.'"

-

Poetry:

- The Lay of the Last Minstrel. 1805. Ed. W. Minto. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1886.

- The Poetical Works. Ed. J. Logie Robertson. Oxford Complete Edition. London: Henry Frowde, 1886.

- The Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. Ed. Andrew Lang. 2 vols. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1897.

- Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. 1830. Introduction by P. G. Maxwell-Stuart. Myth, Legend and Folklore Series. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions, in Association with The Folklore Society, 2001.

- The Journal, 1825-32: From the Original Manuscript at Abbotsford. Ed. David Douglas. Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1891.

- Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border: Consisting of Historical and Romantic Ballads. 1802-3. Ed. Alex. Murray. London: Alex. Murray & Son, 1869.

- J. G. Lockhart. The Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart., 1771-1832. 1836. Complete Edition. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1896.

- Edgar Johnson. Sir Walter Scott: The Great Unknown. Volume 1: 1771-1821. London. Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1970.

- Edgar Johnson. Sir Walter Scott: The Great Unknown. Volume 2: 1821-1832. London. Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1970.

Prose:

Edited:

Secondary:

•

William McGonagall (c.1900)

William Topaz McGonagall

(1825-1902)

I suppose that the inclusion of William Topaz McGonagall in any list of Scottish poets could be taken as a somewhat provocative gesture. He has, after all, become a figure of fun of the type of the singer Florence Foster Jenkins, or the pitiful would-be street artist 'Mr. Brainwash' in Bansky's 2010 documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop.

I suppose that my basic problem - like the man from Missouri - is that I always prefer to see for myself. There's no doubt that McGonagall's work is the most arrant doggerel. But it's strangely readable, even so. What converted me to his cause, though, was the prose narrative included in the 1972 paperback selection from his works, The Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay and Other Disasters.

After he'd written to Queen Victoria, requesting patronage for his work, McGonagall interpreted the polite dismissal he was sent in return as encouragement for his endeavours. He therefore decided to walk from Dundee to Balmoral, letter in hand, to thank her in person for her kindness.

His account of this demanding journey, with the final let-down on arrival when he was refused entry to the castle, has a curiously poignant effect. His sincerity and simplicity somehow combine to make him the hero of the whole affair. It may not be quite on the level of John Clare's 'Journey from Essex', his account of his escape from the asylum in which he was confined and subsequent doomed search for his (long-dead) ex-sweetheart, but it does, at times, have something of the same atmosphere.

Like the Emperor of the United States, Joshua Norton, it can be said of McGonagall that he did no harm, provided amusement for many, and somehow continues to grow larger rather than smaller with the years, unlike most of his more respectable contemporaries.

The Tay Bridge Disaster Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay! Alas! I am very sorry to say That ninety lives have been taken away On the last Sabbath day of 1879, Which will be remember’d for a very long time. ‘Twas about seven o’clock at night, And the wind it blew with all its might, And the rain came pouring down, And the dark clouds seem’d to frown, And the Demon of the air seem’d to say- “I’ll blow down the Bridge of Tay.” When the train left Edinburgh The passengers’ hearts were light and felt no sorrow, But Boreas blew a terrific gale, Which made their hearts for to quail, And many of the passengers with fear did say- “I hope God will send us safe across the Bridge of Tay.” But when the train came near to Wormit Bay, Boreas he did loud and angry bray, And shook the central girders of the Bridge of Tay On the last Sabbath day of 1879, Which will be remember’d for a very long time. So the train sped on with all its might, And Bonnie Dundee soon hove in sight, And the passengers’ hearts felt light, Thinking they would enjoy themselves on the New Year, With their friends at home they lov’d most dear, And wish them all a happy New Year. So the train mov’d slowly along the Bridge of Tay, Until it was about midway, Then the central girders with a crash gave way, And down went the train and passengers into the Tay! The Storm Fiend did loudly bray, Because ninety lives had been taken away, On the last Sabbath day of 1879, Which will be remember’d for a very long time. As soon as the catastrophe came to be known The alarm from mouth to mouth was blown, And the cry rang out all o’er the town, Good Heavens! the Tay Bridge is blown down, And a passenger train from Edinburgh, Which fill’d all the peoples hearts with sorrow, And made them for to turn pale, Because none of the passengers were sav’d to tell the tale How the disaster happen’d on the last Sabbath day of 1879, Which will be remember’d for a very long time. It must have been an awful sight, To witness in the dusky moonlight, While the Storm Fiend did laugh, and angry did bray, Along the Railway Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay, Oh! ill-fated Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay, I must now conclude my lay By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay, That your central girders would not have given way, At least many sensible men do say, Had they been supported on each side with buttresses, At least many sensible men confesses, For the stronger we our houses do build, The less chance we have of being killed.

-

Poetry:

- Poetic Gems / More Poetic Gems / Last Poetic Gems. 1934, 1954 & 1968. Dundee: David Winter & Son Ltd. / London: Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd., 1970.

- The Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay and Other Disasters. London: Sphere Books, 1972.

•

Andrew Young (1885-1971)

Andrew Young

(1885-1971)

I've always had rather a soft spot for the poetry of Andrew Young, though I'm not quite sure why.

Perhaps it's because he manages to write a kind of pastoral poetry which seems to eschew easy sentimentality. I read an interesting review comparing his work to that of the early Pound, given the fact that they were near-contemporaries, but I don't think it's that, exactly.

Partially, I suppose, it's pure nostalgia. The sheer beauty of the 1960 edition of his Collected Poems seems to enshrine the words themselves as something special: little rococo gems embedded in a cabinet of curiosities.

A Dead Mole Strong-shouldered mole, That so much lived below the ground, Dug, fought and loved, hunted and fed, For you to raise a mound Was as for us to make a hole; What wonder now that being dead Your body lies here stout and square Buried within the blue vault of the air?

-

Poetry:

- The Collected Poems of Andrew Young. Bibliographical Note by Leonard Clark. Wood-engravings by Joan Hassall. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1960.

- The Poetical Works. Ed. Edward Lowbury & Alison Young. Wood Engravings by Joan Hassall. London: Secker & Warburg, 1985.

- Parables. Wood Engravings by Joan Hassall. Richmond, Surrey: The Keepsake Press, 1985.

Prose:

•

Edwin Muir (1887-1959)

Edwin Muir

(1887-1959)

Edwin Muir, by contrast, is an author who's fascinated me ever since I first read Kafka's The Castle, which he co-translated with his wife Willa.

After that he seemed to pop up all over the place, as a poet, a novelist, an autobiographer - I'm afraid that I still prefer The Story and the Fable (1940), the first version of his autobiography, to the later, expanded edition, mainly because of its last chapter, a fascinating diary of his thoughts in the late 1930s.

As for his poetry, its apparent simplicity masks a more complex story. When I first started to read it, it was very much what I was looking for: poetry that eschewed bells and whistles in favour of a more subversive, almost childlike agenda.

I'd been encouraged to see Gerard Manley Hopkins and Dylan Thomas as the acme of what verse was capable of. Edwin Muir seemed to offer another solution: the vocabulary of a fairy-tale or a dream, but one based in the remembered reality of a childhood paradise, rural Orkney.

Merlin O Merlin in your crystal cave Deep in the diamond of the day, Will there ever be a singer Whose music will smooth away The furrow drawn by Adam's finger Across the memory and the wave? Or a runner who'll outrun Man's long shadow driving on, Break through the gate of memory And hang the apple on the tree? Will your magic ever show The sleeping bride shut in her bower, The day wreathed in its mound of snow and Time locked in his tower?

-

Poetry:

- Variations on a Time Theme. London: J. M. Dent, 1934.

- The Narrow Place. London: Faber, 1943.

- One Foot in Eden. London: Faber, 1956.

- Collected Poems, 1921-1951. New York: Grove Press, 1957.

- Collected Poems. 1960. 2nd edition. London: Faber, 1963.

- Collected Poems. 1963. London: Faber, 1984.

- The Structure of the Novel. 1928. London: Chatto & Windus, 1979.

- Poor Tom (1932). In Growing Up in the West: Edwin Muir, Poor Tom; J. F. Hendry, Fernie Brae: A Scottish Childhood; Gordon M. Williams, From Scenes Like These; & Tom Gallacher, Apprentice. 1932, 1947, 1968 & 1983. Ed. Liam McIlvanney. Canongate Classics. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2003.

- Scottish Journey. 1935. Introduction by T. C. Smout. 1980. Flamingo. London: Fontana Paperbacks, 1985.

- An Autobiography. 1940. London: The Hogarth Press, 1954.

- Willa Muir. Belonging: A Memoir. London: The Hogarth Press, 1967. [proof copy]

Prose:

Secondary:

•

‘Whaur Extremes Meet’: A Portrait of the poet Hugh MacDiarmid

Christopher Murray Grieve / 'Hugh MacDiarmid'

(1892-1978)

I wouldn't say that I was a MacDiarmid fan exactly, but it's impossible to overlook him if you're trying to do any kind of survey of modern Scottish poetry.

I suppose that part of the problem is that my paternal grandmother came from a long line of Gaelic speaking fishermen from the Highlands and Islands: West coasters through and through. My grandfather, by contrast, came from the Scots-speaking East Coast, but from its northernmost reaches: Dingwall, rather than Edinburgh or Glasgow.

In other words, all our family romanticism was fixated on the Highlands, and Lallans was not part of the equation at all. I therefore have to take MacDiarmid's idiom almost entirely on trust, without any way of judging its poetic appropriateness.

I have enjoyed much of what I've read of him, though - particularly the earlier, less long-winded work. There's a certain verbosity to some of it which is not really to my taste, however.

from A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle The function, as it seems to me, O’ Poetry is to bring to be At lang, lang last that unity ... But wae’s me on the weary wheel! Higgledy-piggledy in’t we reel, And little it cares hoo we may feel. Twenty-six thoosand years ’t’ll tak’ For it to threid the Zodiac —A single roond o’ the wheel to mak’! Lately it turned—I saw mysel’ In sic a company doomed to mell, I micht ha’e been in Dante’s Hell. It shows hoo little the best o’ men E’en o’ themsels at times can ken— I sune saw that when I gaed ben. The lesser wheel within the big That moves as merry as a grig, Wi’ mankind in its whirligig, And hasna turned a’e circle yet Tho’ as it turns we slide in it, And needs maun tak’ the place we get. I felt it turn, and syne I saw John Knox and Clavers in my raw, And Mary Queen o’ Scots ana’, And Rabbie Burns and Weelum Wallace, And Carlyle lookin’ unco gallus, And Harry Lauder (to enthrall us). And as I looked I saw them a’, A’ the Scots baith big and sma’, That e’er the braith o’ life did draw. ‘Mercy o’ Gode, I canna thole Wi’ sic an orra mob to roll.’ —‘Wheesht! It’s for the guid o’ your soul.’ ‘But what’s the meanin’, what’s the sense?’ —‘Men shift but by experience. ’Twixt Scots there is nae difference. They canna learn, sae canna move, But stick for aye to their auld groove —The only race in History who’ve Bidden in the same category Frae stert to present o’ their story, And deem their ignorance their glory. The mair they differ, mair the same. The wheel can whummle a’ but them, —They ca’ their obstinacy “Hame,” And “Puir Auld Scotland” bleat wi’ pride, And wi’ their minds made up to bide A thorn in a’ the wide world’s side. There ha’e been Scots wha ha’e ha’en thochts, They’re strewn through maist o’ the various lots —Sic traitors are nae Langer Scots!’ ‘But in this huge ineducable Heterogeneous hotch and rabble, Why am I condemned to squabble?’ ‘A Scottish poet maun assume The burden o’ his people’s doom, And dee to brak’ their livin’ tomb. Mony ha’e tried, but a’ ha’e failed. Their sacrifice has nocht availed. Upon the thistle they’re impaled. You maun choose but gin ye’d see Anither category ye Maun tine your nationality.’ And I look at a’ the random Band the wheel leaves whaur it fand ’em ‘Auch, to Hell, I’ll tak’ it to avizandum.’ ... O wae’s me on the weary wheel, And fain I’d understand them! And blessin’ on the weary wheel Whaurever it may land them! ... But aince Jean kens what I’ve been through The nicht, I dinna doot it, She’ll ope her airms in welcome true, And clack nae mair aboot it ... * * * * * The stars like thistle’s roses floo’er The sterile growth o’ Space ootour, That clad in bitter blasts spreids oot Frae me, the sustenance o’ its root. O fain I’d keep my hert entire, Fain hain the licht o’ my desire, But ech! the shinin’ streams ascend, And leave me empty at the end. For aince it’s toomed my hert and brain, The thistle needs maun fa’ again. —But a’ its growth ’ll never fill The hole it’s turned my life intill! ... Yet ha’e I Silence left, the croon o’ a’. No’ her, wha on the hills langsyne I saw Liftin’ a foreheid o’ perpetual snaw. No’ her, wha in the how-dumb-deid o’ nicht Kyths, like Eternity in Time’s despite. No’ her, withooten shape, wha’s name is Daith, No’ Him, unkennable abies to faith —God whom, gin e’er He saw a man, ’ud be E’en mair dumfooner’d at the sicht than he —But Him, whom nocht in man or Deity, Or Daith or Dreid or Laneliness can touch, Wha’s deed owre often and has seen owre much. O I ha’e Silence left —‘And weel ye micht,’ Sae Jean’ll say, ‘efter sic a nicht!’

-

Poetry:

- Selected Poems. Ed. David Craig & John Manson. The Penguin Poets. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

- The Complete Poems of Hugh MacDiarmid. Ed. Michael Grieve & W. R. Aitken. 2 vols. 1978. 2nd edition with corrections and an appendix. Penguin Modern Classics. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

- The Thistle Rises: An Anthology of Verse and Prose by Hugh MacDiarmid. Ed. Alan Bold. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1984.

- Alan Bold. MacDiarmid: Christopher Murray Grieve. A Critical Biography. 1988. Rev. ed. Paladin. Grafton Books. London: Collins Publishing Group, 1990.

Prose:

Secondary:

•

Michael Knowles: Sorley Maclean (1911-1996)

Sorley MacLean / Somhairle MacGill-Eain

(1911-1996)

With Sorley MacLean, we begin to enter the field of family mythology. It's not that I'm directly related to him - though if you go back a bit I suppose you'll find every Mackenzie, Maclean, or Macleod linked through clan loyalty if not genealogy.

It is, rather, that the people and places he's writing about - that whole lost culture of Gaelic-speaking Scotland - closely represent the experience of my grandmother's family.

More to the point, my cousin, the artist Will Maclean, has been strongly influenced by Sorley Maclean's poetry, and was indeed the first one to press it on me, long before I understood anything much about the cultural devastation the two of them have set out to record.

But what of the poetry itself? It can be a little hard to judge through the medium of translation, even when those translations were done by the poet himself.

Accordingly, I thought it might be interesting to contrast Seamus Heaney's version of "Hallaig", below, with Sorley Maclean's own version further down:Time, the deer, is in Hallaig Wood

It's hard for me to respond to that line 'Time, the deer, is in Hallaig Wood' the way I do to 'Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig', but then that might be purely through my familiarity with the latter.

There's a board nailed across the window

I looked through to see the west

And my love is a birch forever

By Hallaig Stream, at her tryst

Between Inver and Milk Hollow,

somewhere around Baile-chuirn,

A flickering birch, a hazel,

A trim, straight sapling rowan.

In Screapadal, where my people

Hail from, the seed and breed

Of Hector Mor and Norman

By the banks of the stream are a wood.

To-night the pine-cocks crowing

On Cnoc an Ra, there above,

And the trees standing tall in moonlight -

They are not the wood I love.

I will wait for the birches to move,

The wood to come up past the cairn

Until it has veiled the mountain

Down from Beinn na Lice in shade.

If it doesn't, I'll go to Hallaig,

To the sabbath of the dead,

Down to where each departed

Generation has gathered.

Hallaig is where they survive,

All the MacLeans and MacLeods

Who were there in the time of Mac Gille Chaluim:

The dead have been seen alive,

The men at their length on the grass

At the gable of every house,

The girls a wood of birch trees

Standing tall, with their heads bowed.

Between The Leac and Fearns

The road is plush with moss

And the girls in a noiseless procession

Going to Clachan as always

And coming back from Clachan

And Suisnish, their land of the living,

Still lightsome and unheartbroken,

Their stories only beginning.

From Fearns Burn to the raised beach

Showing clear in the shrouded hills

There are only girls congregating,

Endlessly walking along

Back through the gloaming to Hallaig

Through the vivid speechless air,

Pouring down the steep slopes,

Their laughter misting my ear

And their beauty a glaze on my heart.

Then as the kyles go dim

And the sun sets behind Dun Cana

Love's loaded gun will take aim.

It will bring down the lightheaded deer

As he sniffs the grass round the wallsteads

And his eye will freeze: while I live,

His blood won't be traced in the woods.

There's something a little jog-trot about the rhythm of Heaney's version. The rhymes and half-rhymes don't always seem entirely successful, and the 'lightheaded deer' of his last stanza seems less specific than Sorley's 'deer that goes dizzily'.

All in all, though, where Sorley Maclean's is clearly a version from the Gaelic, Seamus Heaney's sounds more like an English poem. I guess it comes down to whether you're more interested in that than in the sense of a hidden beauty concealed behind the actual words. It's nice to have both, really.

Hallaig "Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig" The window is nailed and boarded through which I saw the West and my love is at the Burn of Hallaig, a birch tree, and she has always been between Inver and Milk Hollow, here and there about Baile-chuiru: she is a birch, a hazel, a straight, slender young rowan. In Screapadal of my people where Norman and Big Hector were, their daughters and their sons are a wood going up beside the stream. Proud tonight the pine cocks crowing on the top of Cnoc an Ra, straight their backs in the moonlight — they are not the wood I love. I will wait for the birch wood until it comes up by the cairn, until the whole ridge from Beinn na Lice will be under its shade. If it does not, I will go down to Hallaig, to the Sabbath of the dead, where the people are frequenting, every single generation gone. They are still in Hallaig, MacLeans and MacLeods, all who were there in the time of Mac Gille Chaluim the dead have been seen alive The men lying on the green at the end of every house that was, the girls a wood of birches, straight their backs, bent their heads. Between the Leac and Fearns the road is under mild moss and the girls in silent bands go to Clachan as in the beginning, and return from Clachan from Suisnish and the land of the living; each one young and light-stepping, without the heartbreak of the tale. From the Burn of Fearns to the raised beach that is clear in the mystery of the hills, there is only the congregation of the girls keeping up the endless walk, coming back to Hallaig in the evening, in the dumb living twilight, filling the steep slopes, their laughter a mist in my ears, and their beauty a film on my heart before the dimness comes on the kyles, and when the sun goes down behind Dun Cana a vehement bullet will come from the gun of hove; and will strike the deer that goes dizzily, sniffing at the grass-grown ruined homes; his eye will freeze in the wood, his blood will not be traced while I live.

-

Poetry:

- Poems to Eimhir: Poems from Dain do Eimhir. 1943. Trans. Iain Crichton Smith. 1971. Newcastle on Tyne: Northern House, 1973.

- Spring Tide and Neap Tide: Selected Poems 1932-72 / Somhairle MacGill-Eain. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977.

- O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. 1989. Manchester: Carcanet Press Limited, 1990.

•

W. S. Graham (1918-1986)

William Sydney Graham

(1918-1986)

W. S. Graham is one of my friend David Howard's favourite poets. And I have to say that the poem below gives you a good idea why.

There's a wonderful, luminous precision about what he writes - at his best, in such works as The Nightfishing (1955), that is.

There are other aspects to him, though. His 1970 collection Malcolm Mooney's Land occupies something of the same despairing territory as Beckett, with its juxtaposition of the language of polar expeditions on the horrid wastes of alcoholic oblivion represented by the real-life pub landlord Malcolm Mooney.

Then there's his long residence in Cornwall, where he moved in 1954, near the artists' colony of St. Ives. Graham was almost their muse at times, finding words for the work of such luminaries as Barbara Hepworth, Roger Hilton, Ben Nicholson and Bryan Wynter. That Apollinaire-like quest may be the side of him that appeals most to David.

W. S. Graham is still not nearly as well known as he should be. He touches on so many categories, but can't be contained by any of them. Isn't that the best kind of poet to be?

Listen. Put on morning Listen. Put on morning. Waken into falling light. A man’s imagining Suddenly may inherit The handclapping centuries Of his one minute on earth. And hear the virgin juries Talk with his own breath To the corner boys of his street. And hear the Black Maria Searching the town at night. And hear the playropes caa The sister Mary in. And hear Willie and Davie Among bracken of Narnain Sing in a mist heavy With myrtle and listeners. And hear the higher town Weep a petition of fears At the poorhouse close upon The public heartbeat. And hear the children tig And run with my own feet Into the netting drag Of a suiciding principle. Listen. Put on lightbreak. Waken into miracle. The audience lies awake Under the tenements Under the sugar docks Under the printed moments. The centuries turn their locks And open under the hill Their inherited books and doors All gathered to distil Like happy berry pickers One voice to talk to us. Yes listen. It carries away The second and the years Till the heart’s in a jacket of snow And the head’s in a helmet white And the song sleeps to be wakened By the morning ear bright. Listen. Put on morning. Waken into falling light.

-

Poetry:

- Collected Poems 1942-1977. London: Faber, 1979.

•

George Mackay Brown (1921-1996)

George Mackay Brown

(1921-1996)

When I finally got to visit the Orkney Islands, I must admit that they did seem imbued with the strange, half-Gaelic, half-Norse atmosphere I'd become accustomed to from reading George Mackay Brown's books: in particular, his novel Magnus (1973).

I couldn't find many traces of Edwin Muir, but Brown seemed to be everywhere: in giftshops, in paintings, in the whole touristic panoply of the place.

I don't mean that critically. It was just a bit odd to find a place where a poet's work seemed so close to the surface, particularly in philistine modernity.

The impulse behind his poetry and his prose does not seem particularly different in kind. The poems are more concentrated, but no more or less lyrical than his prose. But then, if Muir embodies the exile from Eden, Brown animates a no less powerful Scottish archetype: the local bard.

Hamnavoe Market They drove to the Market with ringing pockets. Folster found a girl Who put wounds on his face and throat, Small and diagonal, like red doves. Johnston stood beside the barrel. All day he stood there. He woke in a ditch, his mouth full of ashes. Grieve bought a balloon and a goldfish. He swung through the air. He fired shotguns, rolled pennies, ate sweet fog from a stick. Heddle was at the Market also. I know nothing of his activities. He is and always was a quiet man. Garson fought three rounds with a negro boxer, And received thirty shillings, Much applause, and an eye loaded with thunder. Where did they find Flett? They found him in a brazen circle, All flame and blood, a new Salvationist. A gypsy saw in the hand of Halcro Great strolling herds, harvests, a proud woman. He wintered in the poorhouse. They drove home from the Market under the stars Except for Johnston Who lay in a ditch, his mouth full of dying fires.

-

Poetry:

- Brown, George Mackay. The Collected Poems of George Mackay Brown. Ed. Archie Bevan & Brian Murray. London: John Murray Publishers, 2006.

- Brown, George Mackay. An Orkney Tapestry. Drawings by Sylvia Wishart. 1969. London: Quartet Books, 1974.

- Brown, George Mackay. Greenvoe. 1972. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976.

- Brown, George Mackay. Hawkfall and Other Stories. London: The Hogarth Press, 1974.

- Fergusson, Maggie. George Mackay Brown: The Life. John Murray Publishers. London: Hodder Headline, 2006.

Prose:

Secondary:

•

Douglas Dunn (1942- )

Douglas Eaglesham Dunn

(1942- )

Douglas Dunn is the only one of the poets in this list whom I've actually met. Only in passing, mind you. I was staying with my cousin Will Maclean, whom I mentioned above, and the two of us were conscripted by his neighbour, a colleague from Dundee University, to help shift a large wardrobe from one room to another.

That neighbour turned out to be Douglas Dunn, though I had to admit to him that the only one of his books I'd actually seen in New Zealand was a copy of St. Kilda's Parliament on a remainders table.

He didn't seem unduly distressed by the news. In fact, he seemed a pretty laid-back guy. I imagine the wardrobe shifting must have concluded with a wee dram of some sort, but I don't recall any further details about that.

That would have been 1986 or so, when I first came to Scotland to study, and after that I saw him at readings a couple of times, but not in circumstances where it seemed appropriate to claim acquaintance. He'd just published a book of Elegies for his dead wife, and the death of his friend and mentor Philip Larkin shortly afterwards meant that he was generally roped into memorial services of one kind or another.

I do like his poetry, and his anthology of modern Scottish poetry, and generally liked the lack of sidiness about him - not so common a trait as one might have hoped for in Scotland (or New Zealand, for that matter). Good on him. I hope he's thriving.

Remembering Friends Who Feared Old Age and Dementia More than Death Even when just the other day From Then to Now feels decades away. The name at the back of the mind … What can I say? That memory’s fickle, that fretting Over a lost name or forgotten month Makes you feel guilty, mindless, and blind, That it’s perfectly natural to fear the labyrinth Where the ‘ageing process’ might one day take you Into the land of forgetting? You said it, friends. Too true. Dictionaries become indispensable? There’s an urge to reread the Bible? That song was in what key? Over the hill, Round the corners, round the bends, And nuts to you, too, as I check my diary For wherever it is I’m supposed to be, Today, or the next, that old clock-sorcery I don’t depend on, though I know I should, And which you overdid, old friends. No, I don’t think you did, Not now I’m older. No one Looks forward to being old and alone, The carer with a spoon, Visitor gone, Boredom and fright on television. How do you understand the merry young As you endure a dragging afternoon With a hundred names on the tip of your tongue, Unable to cheer yourself up, In a constant state of indecision? Cheers! Let’s pour another cup.

-

Poetry:

- Terry Street. 1969. London: Faber, 1986.

- Elegies. 1985. London: Faber, 1986.

- Selected Poems 1964-1983. London: Faber, 1986.

- Northlight. London: Faber, 1988.

- Dante’s Drum-kit. London: Faber, 1993.

- Secret Villages. 1985. London: Faber, 1986.

- Dunn, Douglas, ed. The Faber Book of Twentieth-century Scottish Poetry. 1992. London: Faber, 1993.

Prose:

Edited:

•

- category - Scottish Literature: Authors

Subscribe to: Comments (Atom)