William Golding, John Wyndham & Mervyn Peake: Sometime, Never (1956)

William Golding, John Wyndham & Mervyn Peake: Sometime, Never (1956)•

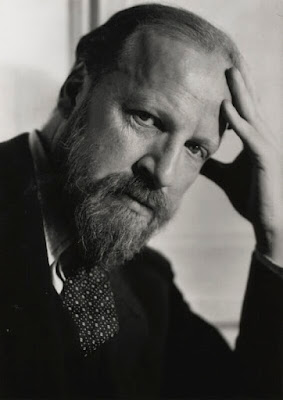

Howard Coster: William Golding (1911-1993)

Howard Coster: William Golding (1911-1993) John Myndham (1903-1969)

John Myndham (1903-1969) Mervyn Peake (1911-1968)

Mervyn Peake (1911-1968)Golding, Wyndham, Peake: Sometime, Never (1956)

[Purchased by my father, Dr. John Mackenzie Ross - Auckland, 1956]:

William Golding, John Wyndham, & Mervyn Peake. Sometime, Never: Three Tales of Imagination. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1956.

You know how it is when you're still considered a little kid when you are - in your own estimation - terribly grown up? I remember one year when my aunt and uncle joined us for Christmas and gave each of us kids - not unreasonably - a children's picture book. We, however, were already deep in The Lord of the Rings and that sort of demanding, close-printed stuff. How gauche of them!

One of the picture books was a bit different from the others, though. It was called Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor, and it was the strangest farrago any of us had ever encountered. It seemed to concern the sudden, unexplained passion of a pirate captain for a weird yellow thing, with whom he decided to set up housekeeping on a desert island instead of continuing his swashbuckling adventures. Edifying? Hardly. Bizarre? Yes. But there was also something quite compelling about the book. It was so perverse, so devoid of the usual saccharine moralising ...

You have to understand that this was long before any of us had encountered the Gormenghast books. Mervyn Peake was not yet a name to conjure with. Once we did start to read them, though, in all their baroque magnificence, Captain Slaughterboard made much better sense. This Peake was no mere concocter of children's picture books, he was one of the elect!

Now, of course - according to Wikipedia:

Peake is considered to be one of the Big Three of Fantasy, along with J. R. R. Tolkien and Robert E. Howard. Their equivalents in the science fiction genre are Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Robert A. Heinlein.Whatever you think of that particular line-up, it certainly puts Peake in some pretty impressive company. They do specify that it's "secondary world" fantasy they have in mind, but even so ... 'considered' by whom, I wonder?

All of which is a rather roundabout way of getting to the book Sometime, Never, which I described as follows in an earlier post on William Golding:

It made a big difference to the reputation (and sales) of a twentieth-century novelist whether or not they were corralled in some 'genre' ghetto, or could be regarded as reliably 'mainstream.'

Golding's inclusion in a 1956 anthology of stories, Sometime, Never, with SF stalwart John Wyndham and Fantasy writer and artist Mervyn Peake, signals his somewhat equivocal status at this early point in his career.

My father, a keen reader of SF paperbacks by the likes of Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein, must have bought this book when it first came out. He already owned a first, 1954 Faber edition of Lord of the Flies, so perhaps it was the Golding connection that clinched it.

On the other hand, he also owned a complete set of John Wyndham paperbacks, from The Day of the Triffids (1951) onwards. Maybe that was it - or maybe it was this unexpected combination of authors which made him decide to buy this one brand new.

One thing's for certain: it wouldn't have been Mervyn Peake who swung the deal. My father did admire his drawings, but found his prose impenetrable and perverse.

The blurb continues as follows:

While that last statement was no doubt accurate when written, 'Consider Her Ways' was included a few years later in Wyndham's collection Consider Her Ways and Others (1961); 'Envoy Extraordinary', too, eventually found a home in William Golding's trio of novellas The Scorpion God (1971).Mervyn Peake, in his story, explores that dreamlike world which, in half a page's reading, becomes more real than the room one is sitting in. The Boy in Darkness is Titus, whom Mervyn Peake's many readers have already met in Titus Groan and Gormenghast, and he is here off on a strange adventure in a country in which no man has ever been but of which many will remember glimpses from their own dreams.

All three stories were specially written for this book and have not previously appeared in print.

It's probably also worth mentioning in this connection that Eyre & Spottiswoode, who put out Sometime, Never, were Peake's publishers, not Golding's (Faber & Faber) or Wyndham's (Michael Joseph).

Perhaps as a result, Mervyn Peake's 'Boy in Darkness' had to wait until 1976 to be republished in book form, in a small standalone edition with an introduction by Peake's widow Maeve Gilmore.

It subsequently reappeared in Gilmore's more comprehensive posthumous anthology, Peake’s Progress; and again, with a corrected text, in Boy in Darkness and Other Stories, his son Sebastian Peake's 'selection of long out-of-print short stories, and never before published illustrations, by one of England's most unique and multi-talented artists.'

The Classic Science Fiction Collection: Fantastic Tales from Jack London, Rudyard Kipling, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, Miles J. Breuer, Austin Hall. Illustrated by Tithi Luadthong. Arcturus Retro Classics. London: Arcturus Publishing Limited, 2018.It's hard now for most of us to understand the virulence of those turf wars over 'mainstream' and 'genre' publication in twentieth-century British and American publishing.

What now seems to us a rather quaint distinction, in an era when popular authors can move from contemporary social chronicles to crime fiction to speculative fiction without surprising - let alone alienating - their core readership, was then seen as a kind of social death.

When writers such as Kingsley Amis attempted to argue for a relaxation of these strict boundaries, he had to be careful not to suggest the admission of anything resembling 'hard' SF to the realms of gold. Instead, in Brian Aldiss's phrase, 'a kind of country-house science fiction' was the best he could expect to encourage.

The principal purveyor of this very English variation on the genre was, of course, John Wyndham.

Which is in itself rather ironic, as - under various pseudonyms, including 'John Beynon' - Wyndham himself had been an assiduous contributor to the plethora of pulp science-fiction magazines which flourished in America (and, to a lesser extent, in the UK) from the 1920s to the late 1940s.

'For more than 100 years, science fiction writers have told tales of alien encounters and fascinating technologies and they have warned of the dangers of dystopian governments. From Victorians experimenting with time travel to pioneers exploring the depths of space, the stories collected here are a tribute to the imagination of the inventors of the modern science fiction genre. Some tales are filled with boundless optimism for the ingenuity of humanity while others provide fearful warnings of the risks of war and the dangers of technology. This collection includes stories from H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, Stanley Weinbaum, Jack London, Austin Hall, and George Griffith amongst others. Includes short stories by such esteemed writers as H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Jack London. Spans the range of the science fiction genre from dystopian futures to deep space adventures to time travel.'The blurb above gives some useful insights into this early understanding of the genre, though the anthology itself probably needs to be supplemented by such books as Asimov's Before the Golden Age: A Science Fiction Anthology of the 1930s, or Mike Ashley's even more comprehensive 4-volume History of the Science-Fiction Magazine: 1926-1965 (1974-78).

Where, then, could the works of Mervyn Peake be said to fit into this genealogy? Well, I suppose they don't, really.

His lifelong addiction to nonsense verses and drawings links him firmly with Edward Lear, also a draughtsman and illustrator by profession. Peake's skill at concocting long and complex narratives, however, suggests an equally strong affinity with Lewis Carroll, all of whose major works he illustrated:

Alongside this taste for nonsense we have Peake's delight in secondary world-building (already mentioned above). This aligns him firmly with Tolkien and E. R. Eddison and all the other pioneers of Epic Fantasy whom I've written about here.

And finally, last but not least, there's the poet. Some, in fact, would see this as the strongest of all his gifts. Certainly the belated publication of his Collected Poems has had the effect of establishing his claims to be rated alongside Dylan Thomas, Philip Larkin and other canonical poets of the 1940s and 50s.

Somehow all of these disparate strands came together in the first two volumes of his masterwork, Gormenghast. I find it difficult, myself, to accept Titus Alone - let alone the posthumous "collaboration" with his wife Maeve Gilmore, Titus Awake - as genuine successors to this original vision of this castle in the middle of nowhere. I leave that question to each reader's own taste to resolve, however.

'Boy in Darkness' does seem to me a worthy addition to the Peake canon, though (along with his wonderful Chestertonian fantasy Mr Pye, and a few of his other short fictions, such as Letters from a Lost Uncle).

Difficult though it is to imagine a visual equivalent for Peake's ornate prose - though his own illustrations certainly do supply vital information about his own conception of the setting and characters of the series - I'm not, myself, nearly as critical of the 2000 BBC TV adaptation as some. The New York Times, for instance:

referred to "viewers' and critics' lukewarm, disappointed response to the series" and while praising "vivid set pieces and characters" judged that it "lacks the narrative pull that would engage viewers with its stylized world."

There may be some truth in that, but the decision by the BBC to based their production design

on the idea that Peake's early life in China had influenced the creation of Gormenghast; thus, the castle in the series resembles the Forbidden City in Beijing as well as the holy city of Lhasa in Tibetwas, to my mind, an inspired one.

Anybody can create a dark, labyrinthine, Gothic castle set: look at most productions of Hamlet. The switch, instead, to the aesthetics of Chinoiserie was immediately refreshing, forcing one to see the whole story in different terms.

The cast, too, was stellar. If I had to choose, I think I would say that Christopher Lee as Mr Flay was himself worth the price of the BBC licencing fee for a whole year. As for the rest, Neve McIntosh was great as Lady Fuchsia, as was Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Steerpike. Perhaps the only weak point (alas) was Titus himself. But then that's a criticism which could probably be directed at the novels, too.

Books I own are marked in bold:

-

Fiction:

- The White Chief of the Unzimbooboo Kaffirs (1921)

- Included in: Peake’s Progress: Selected Writings and Drawings of Mervyn Peake. Ed. Maeve Gilmore. Introduction by John Watney. London: Allen Lane, 1978.

- Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor (Country Life, 1939)

- Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor. Illustrated by the author. 1967. London: Academy Editions, 1977.

- Gormenghast:

- Titus Groan (1946)

- Titus Groan. Illustrated by the author. 1946. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- Included in: The Titus Books: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone. 1946, 1950, 1959. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- Gormenghast (1950)

- Gormenghast. 1950. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974.

- Included in: The Titus Books: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone. 1946, 1950, 1959. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- Boy in Darkness (1956 / 2007)

- Included in: Sometime, Never: Three Tales of Imagination, by William Golding, John Wyndham, & Mervyn Peake. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1956.

- Included in: Peake’s Progress: Selected Writings and Drawings of Mervyn Peake. Ed. Maeve Gilmore. Introduction by John Watney. London: Allen Lane, 1978.

- Included in: Boy in Darkness and Other Stories. Ed. Sebastian Peake (2007)

- Titus Alone (1959)

- Titus Alone. 1959. Rev. ed. 1970. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- Included in: The Titus Books: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone. 1946, 1950, 1959. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983.

- [with Maeve Gilmore] Titus Awakes (2011)

- [with Maeve Gilmore] Titus Awakes: The Lost Book of Gormenghast. Based on a Fragment by Mervyn Peake. Introduction by Brian Sibley. Vintage Books. London: Random House, 2011.

- Titus Groan (1946)

- Letters from a Lost Uncle (from Polar Regions) (1948)

- Letters from a Lost Uncle. Illustrated by the author. 1948. London: Picador, 1977.

- Mr Pye (1953)

- Mr Pye. Illustrated by the author. 1953. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975.

- Boy in Darkness and Other Stories. Ed. Sebastian Peake (2007)

- Boy in Darkness (1956)

- The Weird Journey (1978)

- I Bought a Palm-Tree (1978)

- The Connoisseurs (1978)

- Danse Macabre (1963)

- Same Time, Same Place (1963)

- Shapes and Sounds (1941)

- Rhymes without Reason (1944)

- The Glassblowers (1950)

- Figures of Speech (1954)

- The Rhyme of the Flying Bomb. Illustrated by the author (1962)

- Poems and Drawings (1965)

- A Reverie of Bone and other Poems (1967)

- Selected Poems (1972)

- Selected Poems. 1972. London: Faber, 1981.

- A Book of Nonsense (1972)

- A Book of Nonsense. Illustrated by the author. Introduction by Maeve Gilmore. 1972. London: Picador, 1974.

- Twelve Poems (1975)

- Ten Poems (1993)

- Eleven Poems (1995)

- The Cave (1996)

- Collected Poems. Ed. R. W. Maslen (2008)

- Collected Poems. Ed. R. W. Maslen. Illustrated by the author. Fyfield Books. Manchester: Carcanet Press Limited, 2008.

- Complete Nonsense. Ed. Robert W. Maslen & G. Peter Winnington (2011)

- Complete Nonsense. Ed. R. W. Maslen & G. Peter Winningham. Illustrated by the author. Fyfield Books. Manchester: Carcanet Press Limited, 2011.

- Ride a Cock Horse and Other Nursery Rhymes (1940)

- The Hunting of the Snark, by Lewis Carroll (1941)

- Lewis Carroll. The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony in Eight Fits. Illustrated by Mervyn Peake. 1941. A Zodiac Book. London: Lighthouse Books Ltd., distributed by Chatto & Windus, 1948.

- The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1943)

- The Adventures of The Young Soldier in Search of The Better World, by C. E. M. Joad (1943)

- All This and Bevin Too, by Quentin Crisp (1943)

- Prayers and Graces, by A M Laing (1944)

- Witchcraft in England, by C Hole (1945)

- Quest for Sita, by Maurice Collis (1946)

- The Craft of the Lead Pencil (1946)

- Included in: Writings & Drawings. Ed. Maeve Gilmore & Shelagh Johnson. London: Academy Editions / New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1974.

- Household Tales, by the Brothers Grimm (1946)

- Household Tales by the Brothers Grimm. Illustrated by Mervyn Peake. 1946. London: Methuen, 1973.

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll (1946)

- Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1948)

- Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1949)

- Drawings by Mervyn Peake (1949)

- Thou Shalt not Suffer a Witch, by D. K. Haynes (1949)

- The Swiss Family Robinson, by Johann David Wyss (1950)

- The Book of Lyonne, by Burgess Drake (1952)

- The Young Blackbird, by E. C. Palmer (1953)

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll (1954)

- The Wonderful Life and Adventures of Tom Thumb, by P. B. Austin (1954)

- Men, A Dialogue between Women, by A. Sander (1955)

- More Prayers and Graces, by A. M. Laing (1957)

- The Pot of Gold and Two Other Tales, by A. Judah (1959)

- Droll Stories, by Balzac) (1961)

- The Drawings of Mervyn Peake (1974)

- Extracts from the Poems of Oscar Wilde (1980)

- Oscar Wilde: Extracts from the Poems of Oscar Wilde. Foreword by Maeve Gilmore. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1980.

- Bleak House, by Charles Dickens (1983)

- [with Michael Moorcock] The Sunday Books (2010)

- [with Michael Moorcock] The Sunday Books. 2010. London: Duckworth / New York: Overlook, 2011.

- Writings and Drawings (1974)

- Writings & Drawings. Ed. Maeve Gilmore & Shelagh Johnson. London: Academy Editions / New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1974.

- Peake's Progress (1978)

- Peake’s Progress: Selected Writings and Drawings of Mervyn Peake. Ed. Maeve Gilmore. Introduction by John Watney. London: Allen Lane, 1978.

- Gilmore, Maeve. A World Away: A Memoir of Mervyn Peake. London: Victor Gollancz, 1970.

- Gilmore, Maeve, & Sebastian Peake. Mervyn Peake: Two Lives. ['A World Away: A Memoir of Mervyn Peake', 1970; 'A Child of Bliss', 1989]. Preface by Michael Moorcock. 1983. Foreword by Sebastian Peake. Vintage. London: Random House, 1999.

Poetry & Nonsense:

Art & Illustration:

Miscellaneous:

Secondary:

- category - Fantasy Literature: Authors