Les Murray: Collected Poems (2018)

•

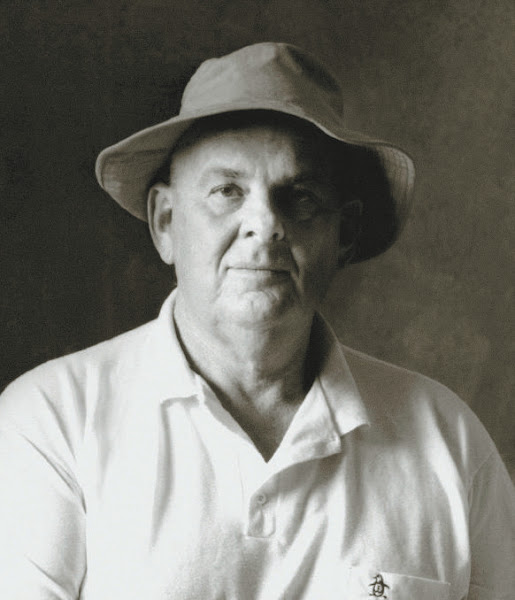

Les Murray (1938-2019)

Les Murray (1938-2019)Les Murray: Collected Poems (2018)

[Hard-to-Find Bookshop, Auckland CBD - purchased 4/4/2022]:

Les Murray. Collected Poems. 2002. Black Inc. Carlton, VIC: Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd, 2018.

To go home and wear shorts foreverMy first acquaintance with the poetry of Les Murray came in the mid-1980s, when I bought a copy of his selected poems, then recently republished by Edinburgh publisher Canongate under the title The Vernacular Republic.

in the enormous paddocks, in that warm climate,

adding a sweater when winter soaks the grass,

to camp out along the river bends

for good, wearing shorts, with a pocketknife,

a fishing line and matches,

or there where the hills are all down, below the plain,

to sit around in shorts at evening

on the plank verandah

Despite being half-Australian (my mother came from Sydney, my father from Rawene in the far North of New Zealand), I've always had a rather equivocal relationship with the Lucky Country. I've visited it frequently, but never felt quite at home there. I did love the cover image and title of the Les Murray collection, though ... what the heck, I decided to buy it. It might not be my Antipodes exactly, but it still felt closer to me than Scotland had proved to be.

One would have to say that Murray was a dab hand at titles: The Vernacular Republic is pretty good, but then so are a lot of others by him: "The Quality of Sprawl", The People's Otherworld, even that late collection Subhuman Redneck Poems. They speak to me. Best of all, perhaps, is the title of the poem I started to quote above, "The Dream Of Wearing Shorts Forever." What Australasian commoner doesn't dream of that? I know I do.

Ideal for getting served lastHow can you resist that? - "to be walking meditatively / among green timber". That's what I'd like to be doing right now, rather than tapping away on this machine. At least I'm wearing shorts, though, and my feet are bare.

in shops of the temperate zone

they are also ideal for going home, into space,

into time, to farm the mind's Sabine acres

for product and subsistence.

Now that everyone who yearned to wear long pants

has essentially achieved them,

long pants, which have themselves been underwear

repeatedly, and underground more than once,

it is time perhaps to cherish the culture of shorts,

to moderate grim vigour

with the knobble of bare knees,

to cool bareknuckle feet in inland water,

slapping flies with a book on solar wind

or a patient bare hand, beneath the cadjiput trees,

to be walking meditatively

among green timber, through the grassy forest

towards a calm sea

and looking across to more of that great island

and the further tropics.

Later on, in the early 1990s, when I was an English tutor at Auckland University, I was asked by Terry Sturm to give a guest lecture on Les Murray and Australian poetry to one of his graduate classes. To paraphrase Ezra Pound's "Villanelle: The Pyschological Hour", I overprepared the event. And that was, indeed, ominous.

I read through reams of Les Murray's critical prose, reprinted in such volumes as The Peasant Mandarin (another good title) and Persistence in Folly, and tried to make sense of all the various polemics he'd penned and controversies he'd been involved in.

It seems, at that stage, that there was a tendency to divide Australian culture into two parallel traditions, labelled by Murray as the Athenian and the Boeotian. The Athenian was the civilised, urban, globalised world of sophisticates such as expatriate Aussie Peter Porter. The Boeotian (named for the most rural and backward of the Greek states) was the world of peasant ritual and ancestral inheritance. As Murray himself put it: the Athenian represents "that perennial urbane country of the mind which for ever scorns, oppresses and renews itself from my native Boeotia."

I found this a fascinating notion, and compiled a huge handout with quotes from Murray's poems and essays alongside parallel passages from Peter Porter (try saying that three times in a row after you've had a few drinks). The students, alas, did not agree. They sat there like stuffed dummies, with their mouths open. Terry thanked me for all my hard work on it later, but admitted that it might have been a trifle above their heads. Never mind, you have to start learning sometime how not to bury your lead. I certainly hope that I could do a better job of getting it across now. But then who knows?

If the cardinal points of costume

are Robes, Tat, Rig and Scunge,

where are shorts in this compass?

... shorts

are farmers' rig, leathery with salt and bonemeal;

are sailors' and branch bankers' rig,

the crisp golfing style

of our youngest male National Costume.

...

shorts and their plain like

are an angelic nudity,

spirituality with pockets!

A double updraft as you drop from branch to pool!

I think I first met Australian poet John Tranter, editor of the experimental journal Jacket, sometime around 2010, when I attended a symposium called Home and Away in Sydney.

Rightly or wrongly, Tranter was regarded by many as the anti-Murray. His Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry (1991), co-edited with Philip Mead, was seen as a counterblast to Murray's New Oxford Book of Australian Verse (1986), stressing the experimental and innovative aspects of the national tradition, rather than Murray's rural pieties.

Glancing through the online archive of Jacket (1997-2010), I find the following, rather characteristic, review by John Redmond of Murray's 1997 volume Subhuman Redneck Poems:

A round, bald man, now in late middle age, Murray is intensely conscious of his lack of physical appeal. At school, he tells us, he had a miserable time mainly because other children mocked his size:This is not, however, seen as any reason for feeling sympathetic towards his plight: "Murray is not trying to convert me or anyone else to his side. He is scarcely even trying to connect. I suspect, therefore, that this is a bad book. I know it leaves me ‘moveless’."... all my names were fat-names, at my new town school.

Between classes, kids did erocide: destruction of sexual morale.

Mass refusal of unasked love; that works. Boys cheered as seventeen-

year-old girls came on to me, then ran back whinnying ridicule.

Twenty-five years on, it seems rather pointless to take sides in this controversy, if controversy it indeed was. Certainly Tranter told me that he harboured no ill feeling towards Murray, and in fact admired much of his work.

In any case, now that we know so much more about Murray's life thanks to Peter Alexander's interesting 2001 biography, not to mention Killing the Black Dog, the poet's own 2009 "memoir of depression", perhaps it makes more sense simply to see him as one of Australia's greatest poets, rather than as some kind of embodiment of belligerent nationalism. The arguments fade, but the poetry remains.

Take, for instance, the poem "An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow", from his 1969 collection The Weatherboard Cathedral:

The word goes round Repins,So when I ran into the latest iteration of his Collected Poems in Hard-to-Find Books the other day, it was natural for me to buy it, despite the fact that I already own two of its predecessors.

the murmur goes round Lorenzinis,

at Tattersalls, men look up from sheets of numbers,

the Stock Exchange scribblers forget the chalk in their hands

and men with bread in their pockets leave the Greek Club:

There’s a fellow crying in Martin Place. They can’t stop him.

The traffic in George Street is banked up for half a mile

and drained of motion. The crowds are edgy with talk

and more crowds come hurrying. Many run in the back streets

which minutes ago were busy main streets, pointing:

There’s a fellow weeping down there. No one can stop him.

The man we surround, the man no one approaches

simply weeps, and does not cover it, weeps

not like a child, not like the wind, like a man

and does not declaim it, nor beat his breast, nor even

sob very loudly – yet the dignity of his weeping

holds us back from his space, the hollow he makes about him

in the midday light, in his pentagram of sorrow,

and uniforms back in the crowd who tried to seize him

stare out at him, and feel, with amazement, their minds

longing for tears as children for a rainbow.

Some will say, in the years to come, a halo

or force stood around him. There is no such thing.

Some will say they were shocked and would have stopped him

but they will not have been there. The fiercest manhood,

the toughest reserve, the slickest wit amongst us

trembles with silence, and burns with unexpected

judgements of peace. Some in the concourse scream

who thought themselves happy. Only the smallest children

and such as look out of Paradise come near him

and sit at his feet, with dogs and dusty pigeons.

Ridiculous, says a man near me, and stops

his mouth with his hands, as if it uttered vomit –

and I see a woman, shining, stretch her hand

and shake as she receives the gift of weeping:

as many as follow her also receive it

and many weep for sheer acceptance, and more

refuse to weep for fear of all acceptance,

but the weeping man, like the earth, requires nothing,

the man who weeps ignores us, and cries out

of his writhen face and ordinary body

not words, but grief, not messages, but sorrow,

hard as the earth, sheer, present as the sea –

and when he stops, he simply walks between us

mopping his face with the dignity of one

man who has wept, and now has finished weeping.

Evading believers, he hurries off down Pitt Street.

... sprawl is full-gloss murals on a council-house wall.He's not my main man by any means, but I do find both the complexities of his work and the varied nature of my engagement with it something I look forward to pondering, more carefully, over time.

Sprawl leans on things. It is loose-limbed in its mind.

Reprimanded and dismissed

it listens with a grin and one boot up on the rail

of possibility. It may have to leave the Earth.

Being roughly Christian, it scratches the other cheek

and thinks it unlikely. Though people have been shot for sprawl.

Books I own are marked in bold:

-

Poetry:

- [with Geoffrey Lehmann] The Ilex Tree (1965)

- The Weatherboard Cathedral (1969)

- Poems Against Economics (1972)

- Lunch and Counter Lunch (1974)

- Selected Poems: The Vernacular Republic (1976)

- Ethnic Radio (1977)

- Equanimities (1982)

- The Vernacular Republic: Poems 1961–1981 (1982)

- The Vernacular Republic: Poems 1961-1981. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1982.

- Flowering Eucalypt in Autumn (1983)

- The People's Otherworld (1983)

- Selected Poems (1986)

- The Daylight Moon (1987)

- The Vernacular Republic: Enlarged Edition (1988)

- The Idyll Wheel (1989)

- Dog Fox Field (1990)

- Dog Fox Field. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1990.

- Collected Poems (1991)

- Collected Poems. A & R Modern Poets. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1991.

- Translations from the Natural World (1992)

- Collected Poems (1994)

- Late Summer Fires (1996)

- Selected Poems (1996)

- Subhuman Redneck Poems (1996)

- Killing the Black Dog (1997)

- New Selected Poems (1999)

- Conscious and Verbal (1999)

- An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow (2000)

- Learning Human: New Selected Poems (2001)

- Poems the Size of Photographs (2002)

- Collected Poems 1961-2002 (2002)

- Collected Poems 1961-2002. CD of selections included. Sydney: Duffy & Snellgrove, 2002.

- The Biplane Houses (2008)

- Taller When Prone (2010)

- The Best 100 Poems of Les Murray (2012)

- New Selected Poems (2014)

- Waiting for the Past (2015)

- On Bunyah (2015)

- Collected Poems (2018)

- Collected Poems. 2002. Black Inc. Carlton, VIC: Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd, 2018.

- Continuous Creation: Last Poems (2022)

- The Boys Who Stole the Funeral (1980)

- The Boys Who Stole the Funeral: A Novel Sequence. 1980. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1982.

- [Les Murray:

- The Boys Who Stole the Funeral: A Novel Sequence. 1980. Manchester, Carcanet, 1989.

- “Notes on the Writing of a Novel Sequence.” Persistence in Folly: Selected Prose Writings 1977-1982. A Sirius Book (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1984): 105-08.]

- Fredy Neptune (1998)

- Fredy Neptune. Sydney: Duffy & Snellgrove, 1998.

- The Peasant Mandarin (1978)

- Persistence in Folly: Selected Prose Writings (1984)

- The Australian Year: The Chronicle of our Seasons and Celebrations (1984)

- Blocks and Tackles (1990)

- The Paperbark Tree: Selected Prose (1992)

- The Quality of Sprawl: Thoughts about Australia (1999)

- A Working Forest: Selected Prose (1997)

- A Working Forest: Selected Prose. Sydney: Duffy & Snellgrove, 1997.

- The Full Dress: An Encounter with the National Gallery of Australia (2002)

- Killing the Black Dog: A Memoir of Depression (2009)

- Anthology of Australian Religious Poetry (1986)

- The New Oxford Book of Australian Verse (1986)

- Fivefathers: Five Australian Poets of the Pre-Academic Era (1994)

- Hell and After: Four Early English-language Poets of Australia (2005)

- Best Australian Poems 2004 (2005)

- The Quadrant Book of Poetry 2001–2010 (2012)

- Alexander, Peter F. Les Murray: A Life In Progress (2001)

Verse Novels:

Prose:

Edited:

Secondary:

•

- category - Australian & Pacific Literature: Australia