Patrick Pearse: Songs of the Irish Rebels (1918)

Patrick Pearse: Songs of the Irish Rebels (1918)•

Pádraig Mac Piarais (1879-1916)

Pádraig Mac Piarais (1879-1916)Patrick Pearse: Songs of the Irish Rebels (1918)

[Finally Books - Hospice Bookshop, Birkenhead - 23/4/24]:

Padraic H. Pearse. Collected Works: Songs of the Irish Rebels and Specimens from an Irish Anthology. Dublin & London: Maunsel and Co., Limited, 1918.

Easter 1916

I wrote a blogpost a few years ago comparing Yeats's immortal "Easter 1916" with some of Seamus Heaney's poems about the Troubles in Northern Ireland:

History says, don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.- from The Cure at Troy (1990)

1916: The Irish Rebellion: 3-part miniseries, created & writ. Bríona Nic Dhiarmada, dir. Pat Collins & Ruan Magan, narrated by Liam Neeson (Ireland, 2016).

Since then I've collected a lot more material on the subject, as well as watching and rewatching the very poignant centenary documentary pictured above. So much courage! so much futility! Talk about "a terrible beauty is born" ...

Every Celtic bone in my body was aching in sympathy as the perfidious English carried poor wounded James Connolly out into the execution yard on a stretcher, tied him to a chair, and shot him, just like all fourteen of the other martyrs (Roger Casement was hanged in London). It brings a tear to my eye even now.

Interestingly enough, though, the last of their three hour-long episodes is titled "When Myth and History Rhyme," presumably as an allusion to Heaney's free adaptation of Sophocles, quoted above.

The Easter Rising certainly is one of the most mythologised events of modern times: perhaps because the Irish have more good poets per square mile than virtually any other country can boast, but also because it remains something of an enigma, even after all this time.

Colin Teevan's recent TV series - another centennial effort - gives a somewhat different slant on 1916. His version of Patrick Pearse (for instance) is a martyr-in-training, cleverly manipulating the English to shoot him for "encouraging the enemy in time of war" instead of convicting him of the lesser offence of "armed insurrection."

The rest of the cast are haplessly swept up in the winds of war and nationalism. All end up more-or-less disillusioned by the end of the drama. It's certainly a coherent approach, but (dare I say it?) Teevan also succeeded in doing something nobody's really managed before, which was to make the Easter Rising seem quite boring.

The central motif of the "three little maids from school" - one a qualified doctor trying to avoid the loveless marriage her wealthy family is foisting on her; another the mistress of a Dublin Castle official, who does a bit of spying on the side, but is really more interested in advancement in the civil service; only the last a genuine fire-breathing fanatic, completely committed to the cause, who only needs to clap on a cloth cap to pass for a man and start shooting traitors - seems more redolent of the world of Downton Abbey than that of Cathleen ni Houlihan.

Did that play of mine send outYeats asked himself in "The Man and the Echo" (1938). I think it's safe to say that Colin Teevan's efforts seem most unlikely to have a similar effect. But then, maybe that's a good thing - maybe bored is better than dead.

Certain men the English shot?

In any case, there's nothing particularly new in this deliberate undercutting of the myths of 1916. Teevan's TV series certainly recalls (possibly even references) Sean O'Casey's classic play The Plough and the Stars, booed at its first performance for its juxtaposition of what Yeats referred to as "the normal grossness of life" - a public house with a prostitute waiting for clients - with the inflated aspirations of the new republic, embodied in its battle standards: the tricolour flag of the Irish Volunteers and the plough-and-stars flag of the Irish Citizen Army.

On that occasion, too, Yeats stood up to harangue the Abbey Theatre rioters:

I thought you had tired of this ... But you have disgraced yourselves again. Is this going to be a recurring celebration of Irish genius? Synge first and then O'Casey.- Wikipedia: The Plough and the Stars

Yeats himself, in his final play "The Death of Cuchulain", included a final chorus equating the death of the mythic Irish hero with those of the martyrs of 1916:

Are those things that men adore and loathe

Their sole reality?

What stood in the Post Office

With Pearse and Connolly?

What comes out of the mountain

Where men first shed their blood?

Who thought Cuchulain till it seemed

He stood where they had stood?

No body like his body

Has modern woman borne,

But an old man looking back in life

Imagines it in scorn.

A statue's there to mark the place,

By Oliver Sheppard done.

So ends the tale that the harlot

Sang to the beggar-man.

Yeats refers again to Sheppard's Michelangelo-esque bronze in another late poem, “The Statues” (1938):

When Pearse summoned Cuchulain to his sideFor myself, I'm still in two minds about it all. Before settling for these bathetic undercuttings as the last word on the Easter Rising, though, I'd urge you to click on the youtube link below, under the image from Ken Loach's wonderful BBC drama Days of Hope (1975), and see if you can resist the beauty of Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill's rendition of "The Bold Fenian Men."

What stalked through the post Office? What intellect,

What calculation, number, measurement, replied?

We Irish, born into that ancient sect

But thrown upon this filthy modern tide

And by its formless spawning fury wrecked,

Climb to our proper dark, that we may trace

The lineaments of a plummet-measured face.

Loach may have borrowed the idea for this scene from the ending of Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory (1957), but I can't help feeling that Loach's version is even more powerful and poignant.

•

Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill: "The Bold Fenian Men" (traditional)

Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill: "The Bold Fenian Men" (traditional)Ken Loach: Days of Hope (BBC, 1975)

The Bold Fenian Men

(1916)

- Roger Casement

- Thomas MacDonagh

- Sean O'Casey

- Patrick Pearse

- James Stephens

- W. B. Yeats

- Anthologies & Secondary Literature

Books I own are marked in bold:

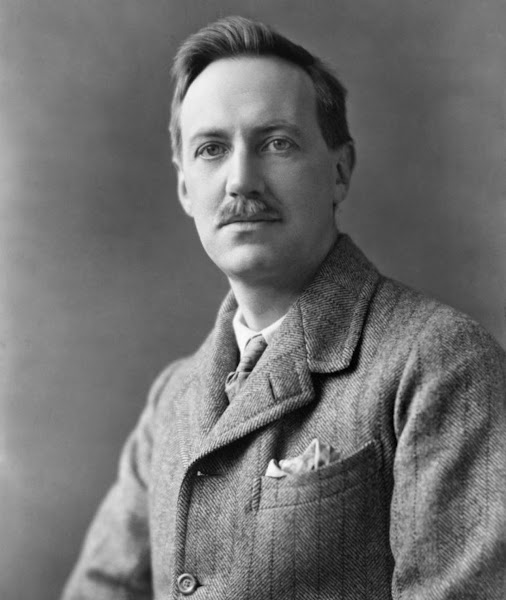

Sarah Purser: Roger Casement (1914)

Sarah Purser: Roger Casement (1914)

Roger David Casement

[Ruairí Mac Easmainn / Sir Roger Casement]

[Ruairí Mac Easmainn / Sir Roger Casement]

(1864-1916)

There's small chance that the execution of Sir Roger Casement will ever cease to be a subject of controversy.

On the one hand, he was a renowned humanitarian, famous for exposing the genocidal crimes of the Belgian King Leopold's colonial regime in the Congo, and then doing much the same thing for the monstrous abuses of the Rubber Barons on the Amazon. He was knighted for these brave exploits.

On the other hand, he was a rabid Irish patriot, caught trying to smuggle guns into Ireland after landing there from a German submarine just before the Easter rising.

Lest these two truths cancel each other out, however, the Crown Prosecutors at his trial deliberately leaked passages from his private diaries which implied that he was an active homosexual. In his novel about Casement, The Dream of the Celt (2010), Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa tries to argue that these passages were simply sex fantasies, rather than the records of actual pick-ups. Most commentators see this as a cop-out, however.

Casement is thus a double martyr: ostensibly convicted for treason, but actually condemned for being a homosexual. It's hard, looking through modern eyes, to see him as anything but a hero.

-

Writings:

- Sir Roger Casement's Heart of Darkness: The 1911 Documents Ed. Angus Mitchell (1999)

- Slavery in Peru: Message from the President of the United States Transmitting Report of the Secretary of State, with Accompanying Papers, Concerning the Alleged Existence of Slavery in Peru (1913)

- The Crime against Ireland, and How the War May Right it (1914)

- Ireland, Germany and Freedom of the Seas: A Possible Outcome of the War of 1914 (2005)

- The Crime against Europe. The Causes of the War and the Foundations of Peace (1915)

- Gesammelte Schriften. Irland, Deutschland und die Freiheit der Meere und andere Aufsätze (1916-17)

- Some Poems (1918)

- Singleton-Gates, Peter & Maurice Girodias. The Black Diaries: An Account of Roger Casement's Life and Times wth a Collection of His Diaries and Public Writings. Paris: The Olympia Press, 1959.

- The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement. Ed. Angus Mitchell. Dublin: The Lilliput Press, Ltd. / London: Anaconda Editions, 1997.

- Roger Casement's Diaries: 1910. The Black and the White. Ed. Roger Sawyer. London: Pimlico, 1997.

- One Bold Deed of Open Treason: The Berlin Diary of Roger Casement. 1914-16. Ed. Angus Mitchell. Dublin: Irish Academic Press / Merrion Press, 2016.

- Hyde, H. Montgomery. Famous Trials, Ninth Series: Roger Casement. 1960. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964.

- MacColl, René. Roger Casement. 1956. A Four Square Biography. London: Landsborough Publications Limited, 1960.

- Vargas Llosa, Mario. The Dream of the Celt. ['El sueño del celta', 2010]. Trans. Edith Grossman. London: Faber, 2012.

Diaries:

Secondary:

This man had kept a schoolThe first of the two men listed in Yeats's "Easter 1916" is Patrick Pearse, who ran the school at St. Enda where Gaelic language and culture were taught. Our "wingèd horse" is presumably a reference to Pegasus, as Pearse was himself a poet and writer of short stories in both English and Irish.

And rode our wingèd horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

The second is Thomas MacDonagh, whose plays had been put on in Yeats' and Lady Gregory's Abbey Theatre, and elsewhere, and whose lyric poetry was widely read - more after the rebellion than before it, admittedly.

The reasons for executing him seem more than usually spurious in this case, as his role in the rising was not particularly central. In retrospect, they should have shot Michael Collins or Éamon de Valera instead. No doubt they would have done, if it hadn't been for the fact that the latter was an American citizen and the former not yet as widely known - and feared - as he soon would be.

-

Poetry:

- Through the Ivory Gate (1902)

- April and May, with Other Verse (1903)

- The Golden Joy (1906)

- Songs of Myself (1910)

- Lyrical Poems (1913)

- Poems (1917)

- The Poetical Works of Thomas MacDonagh. Introduction by James Stephens. London: T. Fisher Unwin Ltd., 1917.

- When the Dawn is Come (1908)

- Metempsychosis (1912)

- Pagans (1915)

- Thomas Campion and the Art of English Poetry (1913)

- Literature in Ireland: Studies Irish and Anglo-Irish (1916)

Plays:

Prose:

"At the onset, O’Casey was a fanatical Irish republican nationalist. Born into an educated, but poverty-stricken family, he had only three years of school education, and became an undernourished unskilled labourer. At the time, the infant mortality rate in Dublin was higher than in Moscow or Calcutta. Despite a serious eye ailment, he educated himself, becoming an avid reader of literature. At an early age, he became an activist in the Gaelic League, the Irish Republican Brotherhood and other nationalist groupings. But because of his situation as a worker, it was almost inevitable that his artistic development would largely depend on the evolution of the socialist movement."O'Casey therefore saw the nationalist struggle begun in 1916 as a betrayal of the socialist ideals of the Irish Citizen Army. The class struggle between capitalists and workers remained, in his view, unaffected by the subsequent Treaty and Civil War.- Dombrovski: "Sean O'Casey and the 1916 Easter Rising." International Communist Current (2006)

Perhaps, then, there's something to be said for Dombrovski's view that O'Casey's "later artistic decline was linked to the perversion of [proletarian] principles with the defeat of the world revolution in the 1920s (O’Casey became an unapologetic Stalinist)." His 1926 play The Plough and the Stars - subsequently turned into a somewhat saccharine Hollywood movie - remains one of the most powerful works inspired by 1916, however.

- [as Seán Ó Cathasaigh] Lament for Thomas Ashe (1917)

- [as Seán Ó Cathasaigh] The Story of Thomas Ashe (1917)

- [as Seán Ó Cathasaigh] Songs of the Wren (1918)

- [as Seán Ó Cathasaigh] More Wren Songs (1918)

- The Harvest Festival (1918)

- [as Seán Ó Cathasaigh] The Story of the Irish Citizen Army (1919)

- The Shadow of a Gunman (1923)

- Included in: Three Plays: Juno and the Paycock / The Shadow of a Gunman / The Plough and the Stars. 1925 & 1926. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1962.

- Kathleen Listens In (1923)

- Juno and the Paycock (1924)

- Included in: Three Plays: Juno and the Paycock / The Shadow of a Gunman / The Plough and the Stars. 1925 & 1926. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1962.

- Nannie's Night Out (1924)

- The Plough and the Stars (1926)

- Included in: Three Plays: Juno and the Paycock / The Shadow of a Gunman / The Plough and the Stars. 1925 & 1926. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1962.

- The Silver Tassie (1927)

- Included in: Three More Plays: The Silver Tassie / Purple Dust / Red Roses for Me. 1928, 1940 & 1942. Introduction by J. C. Trewin. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd. / New York: St. Martin’s Press Inc., 1965.

- Within the Gates (1934)

- The End of the Beginning (1937)

- Included in: Five One-Act Plays: The End of the Beginning / A Pound on Demand / Hall of Healing / Bedtime Story / Time To Go. St. Martin’s Library. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- A Pound on Demand (1939)

- Included in: Five One-Act Plays: The End of the Beginning / A Pound on Demand / Hall of Healing / Bedtime Story / Time To Go. St. Martin’s Library. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- I Knock at the Door (1939)

- Included in: Autobiographies, Volume I: I Knock at the Door / Pictures in the Hallway / Drums Under the Windows. 1939, 1942, 1945. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1963.

- Purple Dust (1940)

- Included in: Three More Plays: The Silver Tassie / Purple Dust / Red Roses for Me. 1928, 1940 & 1942. Introduction by J. C. Trewin. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd. / New York: St. Martin’s Press Inc., 1965.

- The Star Turns Red (1940)

- Pictures in the Hallway (1942)

- Included in: Autobiographies, Volume I: I Knock at the Door / Pictures in the Hallway / Drums Under the Windows. 1939, 1942, 1945. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1963.

- Red Roses for Me (1942)

- Included in: Three More Plays: The Silver Tassie / Purple Dust / Red Roses for Me. 1928, 1940 & 1942. Introduction by J. C. Trewin. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd. / New York: St. Martin’s Press Inc., 1965.

- Drums Under the Window (1945)

- Included in: Autobiographies, Volume I: I Knock at the Door / Pictures in the Hallway / Drums Under the Windows. 1939, 1942, 1945. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1963.

- Oak Leaves and Lavender (1946)

- Cock-a-Doodle Dandy (1949)

- Inishfallen, Fare Thee Well (1949)

- Autobiography, Book 4: Inishfallen, Fare Thee Well. 1949. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1972.

- Hall of Healing (1951)

- Included in: Five One-Act Plays: The End of the Beginning / A Pound on Demand / Hall of Healing / Bedtime Story / Time To Go. St. Martin’s Library. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- Bedtime Story (1951)

- Included in: Five One-Act Plays: The End of the Beginning / A Pound on Demand / Hall of Healing / Bedtime Story / Time To Go. St. Martin’s Library. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- Time to Go (1951)

- Included in: Five One-Act Plays: The End of the Beginning / A Pound on Demand / Hall of Healing / Bedtime Story / Time To Go. St. Martin’s Library. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- Rose and Crown (1952)

- Autobiography, Book 5: Rose and Crown (1926-1934). 1952. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1973.

- The Wild Goose (1952)

- Sunset and Evening Star (1954)

- Autobiography, Book 6: Sunset and Evening Star (1934-1953). 1954. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1973.

- The Bishop's Bonfire: A Sad Play within the Tune of a Polka (1955)

- Mirror in My House: Autobiographies. 2 vols (1956)

- Autobiographies, Volume I: I Knock at the Door / Pictures in the Hallway / Drums Under the Windows. 1939, 1942, 1945. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1963.

- The Drums of Father Ned (1957)

- Behind the Green Curtains (1961)

- Figuro in the Night (1961)

- The Moon Shines on Kylenamoe (1961)

- Niall: A Lament (1991)

- O’Casey, Eileen. Sean. Ed. J. C. Trewin. 1971. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1973.

Secondary:

•

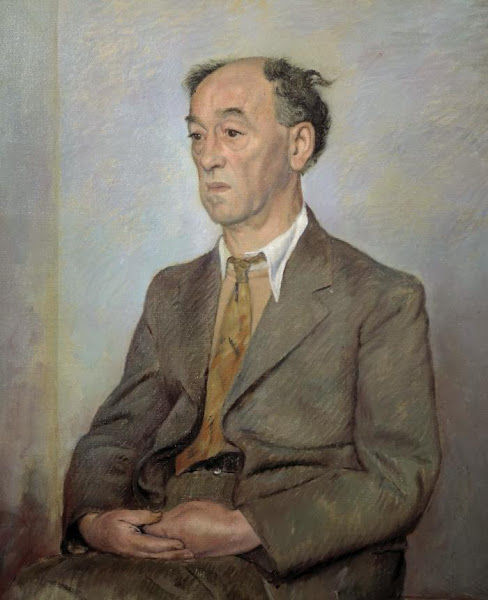

Patrick Pearse (c.1915)

Patrick Pearse (c.1915)

Patrick Henry Pearse

[Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais / An Piarsach]

[Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais / An Piarsach]

(1879-1916)

Pearse is in many ways the most enigmatic of the Easter martyrs. He can be read as a political naïf, so obsessed with the ancient glories of the Gaelic past that he forgot the realities of modern Ireland. Or, alternatively, he can be seen as a clever manipulator of public opinion, deliberately mounting a hopeless rebellion in order to provoke the English to retaliate brutally. His collected works do little to resolve the question. In the end, it's hard to see that it makes much difference. Whether he was sincerely misguided or cunningly far-sighted, his complete failure as a military leader paved the way for the total success of his overall strategy.Some died by the glensideHe gave his life for his beliefs, in any case.

some died mid the stranger

And wise men have told us

their cause was a failure

But they loved dear old Ireland

and never feared danger

Glory O, Glory O

to the bold Fenian men

- The Collected Works of Padraic H. Pearse. Ed. Desmond Ryan. 6 vols (1917-1922)

- Plays, Poems and Stories

- Plays, Stories, Poems. 1917. Dublin & London: Maunsel and Co., Limited, 1919.

- St. Enda and Its Founders

- Songs of the Irish Rebels

- Songs of the Irish Rebels and Specimens from an Irish Anthology. Dublin & London: Maunsel and Co., Limited, 1918.

- Scribhini [Gaelic writings]

- Political Writings and Speeches

- The Life of Patrick H. Pearse. Adapted from the French of Louis N. Le Roux and Revised by the Author. Translated into English by Desmond Ryan.

- Plays, Poems and Stories

"James Stephens (1880–1950) made his name with The Crock of Gold (1912), a story for children of all ages, creating ‘a world of rich fantasy’. He went to Paris in 1912, and in 1915 became Registrar of the National Gallery of Ireland. During Easter week 1916, Stephens witnessed the fighting around St Stephen’s Green, and soon after published an account of his observations: The Insurrection in Dublin."As well as this short account of Easter week, Stephen also wrote an introduction for Thomas MacDonagh's Poetical Works (1917), and published his own book of translations and versions of traditional Irish poems - Reincarnations - in 1918. This was one of various 1916-related books I found in the Hospice shop the other day, along with works by Pearse and W. B. Yeats.- Dr Brendan Rooney: "James Stephens, the National Gallery of Ireland,

and the 1916 Rising." National Gallery of Ireland (2016)

-

Poetry:

- Reincarnations. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1918.

- Collected Poems. 1926. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1931.

- The Insurrection in Dublin (1916)

- James Stephens: A Selection. Ed. Lloyd Frankenberg. Preface by Padraic Colum. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1962.

Prose:

"W. B. Yeats's iconic poem 'Easter 1916' will feature widely during this centenary year of the Easter Rising.Yeats was in London at the time of the rising, and was reported to have said that he was “overwhelmed by the news … [and] had no idea that a public event could move him so deeply.”

It is a many-layered work, but is essentially a love poem to Maud Gonne, whom the poet still hoped to capture. Maud rejected the poem in a famous letter to Yeats, writing, 'No, I don't like your poem, it isn't worthy of you and above all it isn't worthy of your subject.'

She objects to the line 'Too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart' in reference to the Rising, but also to herself. Scholars have concentrated on this metaphor, but omit the other plainly stated reason she rejected the poem further along in her letter. Maud had sought a rapprochement with her husband John MacBride in 1910 but was rebuffed. After his execution, there was no obstacle, though Yeats's unwelcome poem stirs the old feud.

She tells him, and posterity: 'As for my husband he has entered Eternity by the great door of sacrifice which Christ opened & has therefore atoned for all so that in praying for him I can also ask for his prayers & "a terrible beauty is born".' Maud herself may well have been atoning for all to her late husband, John MacBride, in this remarkable sentence."- Anthony J. Jordan, "Letter to the Editor." Irish Independent (8/1/2016)

Having initially stated in "On being asked for a war poem": ‘“I think it better that in times like these a poet keep his mouth shut…” (quoted in K. Alldritt, W. B. Yeats: The Man and the Milieu, 1997), he had subsequently experienced the bombing of London by Zeppelins, and then been even more shocked by the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania, on which he had once travelled, by German submarines.

The treatment of the Easter 1916 prisoners had the effect of galvanising him into making a stand. This may well have been at least partly motivated by the desire to impress his old flame Maud Gonne, but the results certainly went far beyond that, witness his subsequent poem "Sixteen Dead Men":O but we talked at large before

The sixteen men were shot,

But who can talk of give and take,

What should be and what not

While those dead men are loitering there

To stir the boiling pot?

You say that we should still the land

Till Germany’s overcome;

But who is there to argue that

Now Pearse is deaf and dumb?

And is their logic to outweigh

MacDonagh’s bony thumb?

-

Poetry:

- Collected Poems. 1933. Second edition. 1950. London: Macmillan Limited, 1967.

- Collected Plays. 1934. Second edition. London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1952.

- The Death of Cuchulain: Manuscript Materials Including the Author's Final Text. Ed. Phillip L. Marcus. The Cornell Yeats: Plays ed. David R. Clark. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1982.

- Autobiographies: Reveries over Childhood and Youth; The Trembling of the Veil; Dramatis Personae; Estrangement; The Death of Synge; The Bounty of Sweden. 1916, 1922, 1935, 1926, 1928, 1938, 1955. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd., 1956.

- Memoirs: Autobiography – First Draft / Journal. Ed. Denis Donoghue. London: Macmillan Limited, 1972.

- Explorations: Explorations I / The Irish Dramatic Movement: 1901-1919 / Explorations II / Pages from a Diary Written in Nineteen Hundred and Thirty: 1944 / From Wheels and Butterflies: 1934 / From On the Boiler: 1939. Selected by Mrs. W. B. Yeats. London: Macmillan & Co Ltd., 1962.

- White, Anna MacBride, & A. Norman Jeffares, ed. Always Your Friend: The Gonne-Yeats Letters: 1893-1938. 1992. London: Pimlico, 1993.

Plays:

Prose:

Letters:

This is a very summary list of the works which could be cited on this subject. Between them, Max Caulfield's classic history The Easter Rebellion and Robert Kee's The Green Flag give a pretty good overview of the events themselves. Declan Kibber's book gives some useful insights into the ways it's been incorporated into the modern vision of Ireland.

- Bell, J. Bowyer. The Secret Army: A History of the IRA, 1915-1970. 1970. London: Sphere Books Ltd., 1972.

- Caulfield, Max. The Easter Rebellion. 1963. A Four Square Book. London: The New English Library Limited, 1965.

- Kee, Robert. The Green Flag. 1972. 3 vols. London: Quartet Books, 1976.

- The Most Distressful Country

- The Bold Fenian Men

- Ourselves Alone

- Kennelly, Brendan, ed. The Penguin Book of Irish Verse. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

- Kiberd, Declan. Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation. 1995. Vintage. London: Random House, 1996.

- McCourt, Malachy, ed. Voices of Ireland: Classic Writings of a Rich and Rare Land. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2002.

•

- category - Irish Literature: Authors