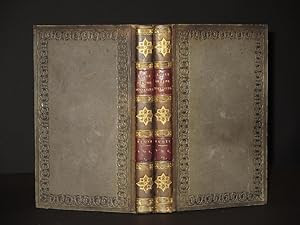

John Sutherland: Lives of the Novelists (2011)

John Sutherland: Lives of the Novelists (2011)•

John Sutherland (1938- )

John Sutherland (1938- )John Sutherland: Lives of the Novelists (2011)

[Hospice Shop. Te Hana - 9/4/24]:

John Sutherland. Lives of the Novelists: A History of Fiction in 294 Lives. London: Profile Books Ltd., 2011. 832 pp.

Rival Lives

The stated exemplar for the 294 entries in Professor John Sutherland's massive Lives of the Novelists is Sir Walter Scott's earlier book of the same title. I can't help thinking that both Sutherland and Sir Walter must have had a far more famous predecessor in mind:

Dr. Samuel Johnson. The Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets; with Critical Observations on Their Works. 1779-81. 4 vols. Ed. Roger Lonsdale. Oxford English Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Johnson's Lives of the Poets is one of those classics more honoured in the breach than the observance. The majority of the 52 poets included are obscure seventeenth and eighteenth century nobodies, whose respective prowess at turning heroic couplets is of little interest to modern readers.

Mind you, Johnson's Lives was itself an imitation of earlier models. Not only did it directly echo Giorgio Vasari's immensely influential Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550-1568), but also a number of classical works in the same vein: Suetonius himself compiled a Lives of the Poets alongside his more famous biographies of The Twelve Caesars.

And yet, if you do persevere with the good Doctor, you'll find a mine of acute and pithy observations on poetry and writing in general. His collection also includes the disproportionately long (considering the latter's merits as a poet) "Life of Savage", which was written some years earlier and remains an undying classic of the biographer's art.

Richard Holmes. Dr Johnson & Mr Savage. 1993. Flamingo. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1994.

In fact, the only real rival to Johnson's "Life of Savage" is Richard Holmes' fascinating life of Johnson's life. Holmes succeeds in teasing out many of the subtleties and elisions in Johnson's seemingly frank and open narrative.

•

In any case, to return to John Sutherland's massive tome, within a few years a couple of competitors were giving it a run for its money:

Thomas G. Pavel. The Lives of the Novel: A History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013. 360 pp.

Michael Schmidt. The Novel: A Biography. Cambridge, Mass & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014. 1200 pp.

As you can see from their respective page-totals, only Michael Schmidt's book aspires to provide coverage on the scale of Sutherland's.

Thomas J. Pavel's, originally published in French as La Pensée du Roman is more of an attempt to define the idea of a novel than a serious effort to list a signficant number of examples, though he does analyze more than a hundred works in this, his history of the novel "from its beginnings in ancient Greece to the second half of the twentieth century".

Michael Schmidt, the Mexican-British author of the second book pictured above, is a far more serious contender. For a start he is himself a poet, as well as the founder (in 1969) of Carcanet Press, an invaluable imprint which continues to champion the reputations of any number of neglected and overlooked poets, from Robert Southwell and John Clare to Ivor Gurney and Robert Graves. The fact that these writers' works remain available at all is, in many cases, down to the dedication of Carcanet and its editors.

This feisty, revisionist attitude comes through even in such stupifyingly inclusive works of scholarship as the following:

Not that Schmidt himself appears to fear competition in his chosen field of the bumper compendium. He is, after all, the author of a direct successor to Dr Johnson's immortal work:

- Lives of the Poets (1998)

- The Story of Poetry. 3 vols (2001-2006):

- From Cædmon to Caxton

- From Skelton to Dryden

- From Pope to Burns

- The First Poets: Lives of the Ancient Greek Poets (2004)

- The Novel: A Biography (2014)

Michael Schmidt. Lives of the Poets. Weidenfield & Nicolson. London: The Orion Publishing Group Ltd., 1998. 992 pp.

which was rapidly followed by:

Ian Hamilton. Against Oblivion: Some Lives of the Twentieth-Century Poets. 2002. London: Penguin, 2003. 336 pp.

John Sutherland. The Literary Detective: 100 Puzzles in Classic Fiction. Cartoons by Martin Rowson. 1996, 1997 & 1999. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. 782 pp.

From the point of view of the common reader, such a plethora of massive works purporting to cover much the same territory can only be seen as a good thing. In the case of Sutherland and Schmidt's respective visions of the novel, it's perhaps useful here to point out their very different backgrounds.

Eminent British Academic and critic John Sutherland is probably best known for a series of entertaining books under the collective title of 'The Literary Detective' in which he attempts to unravel various bookish mysteries with the help of a few reference books and a bit of common sense:

He brings much the same robust attitude to the 294 novelists he's chosen to feature in his huge tome, refusing to exclude such popular writers as Stephen King and Alistair Maclean, but not awarding them a free pass for any of their (alleged) literary misdemeanours, either.

- Is Heathcliff a Murderer? Puzzles in Nineteenth-century Fiction (1996)

- Can Jane Eyre Be Happy? More Puzzles in Classic Fiction (1997)

- Where Was Rebecca Shot? Puzzles, Curiosities and Conundrums in Modern Fiction (1998)

- Who Betrays Elizabeth Bennet? Further Puzzles in Classic Fiction (1999)

The result could be described as bracing or irritating, depending on your temperament. I do find his verdicts on some of the most masterly writers of the last few centuries a little cocksure at times, but at least he's no respecter of bloated reputations.

So which of these works would I recommend? That's a difficult question. For a start, the deplorable tendency of so many writers to employ the term "the novel" to mean the novel in English certainly undermines the utility of many such books.

A more practical objective, then, might be to provide a brief list of some recent contributions to the subject, with notes on their respective approach and coverage. After all, not only novelists but novel-critics do have certain traits in common:

- Ernest A. Baker: The History of the English Novel (1924-1936)

- Ian Watt: The Rise of the Novel (1957)

- Margaret Doody: The True Story of the Novel (1996)

- Thomas G. Pavel: The Lives of the Novel: A History (2003 / 2013)

- Steven Moore: The Novel: An Alternative History (2010 & 2013)

- John Sutherland: Lives of the Novelists (2011)

- Michael Schmidt: The Novel: A Biography (2014)

Coda - Jack Ross: The True Story of the Novel (2013-14)

Books I own are marked in bold:

Ernest A. Baker. The History of the English Novel. 10 vols. 1924-36. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1968-69.

- The Age of Romance: From the Beginnings to the Renaissance (1924)

- The Elizabethan Age and After (1936)

- The Later Romances and the Establishment of Realism (1929)

- Intellectual Realism: From Richardson to Sterne (1936)

- The Novel of Sentiment and the Gothic Romance (1929)

- Edgeworth, Austen, Scott (1929)

- The Age of Dickens and Thackeray (1936)

- From the Brontës to Meredith: romanticism in the English Novel (1936)

- The Day before Yesterday (1936)

- Yesterday (1936)

~

Ernest Baker's standard history of the English novel is, admittedly, a bit out-of-date, but it does have the merit of inclusiveness and thoroughness. It's perhaps more of a museum piece than a serious research tool now, but the early volumes, in particular, cover a good deal of territory which subsequent historians have tended to leave out.

Critical reactions:

One of the most comprehensive studies of the English novel ever written, this book offers a detailed analysis of the genre from its origins to the early 20th century. A landmark work of literary criticism and an important contribution to our understanding of the evolution of the novel.

Only a study of this kind can impress upon us how very slow the development of the modern novel was, how long it had to wait for the propitious moment to emerge as a distinct form of writing. As Dr. Baker says, if the Elizabethans had evolved the novel, it would have been of a very different type from that of Richardson and Fielding. The needs which the novel came to satisfy were not existent; for the major needs of literature were all satisfied by the drama. Therefore the Elizabethan “novel” takes two forms: the artificial and sterile form of Sidney and Lyly; and the popular journalism of Deloney and the pamphleteers: it is the latter which provides the real origins. Elizabethan fiction, in Dr. Baker’s words, is “an obscure, slight, and unsatisfactory affair”.- The Times Literary Supplement, 1434 (25 July 1929): 589.

Ian Watt. The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding. 1957. Peregrine Books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966.

~

Ian Watt's classic book on the rise of the eighteenth-century English novel still dominates a great deal of the discussion on the subject. There are a lot of readers out there who are actually unaware of the fact that Watt's central thesis - that the advent of the bourgeois novel represented a decisive break with the extensive prose fictions of the past - has proved difficult to sustain: particularly if one's reading extends outside the deceptively straightforward province of English literature.

Critical reactions:

The Rise of the Novel is Ian Watt's classic description of the interworkings of social conditions, changing attitudes, and literary practices during the period when the novel emerged as the dominant literary form of the individualist era.

In a new foreword, W. B. Carnochan accounts for the increasing interest in the English novel, including the contributions that Ian Watt's study made to literary studies: his introduction of sociology and philosophy to traditional criticism.- The Rise of the Novel: Updated Edition, University of California Press, 2001.

As the late Robert Folkenflik wrote in a notable review essay in these pages, Ian Watt’s 1957 The Rise of the Novel “has exerted a remarkable hold on the imagination of those writing about the eighteenth-century novel.” Watt is “the man who came to dinner” — and stayed, as Michael Seidel quipped. Despite The Rise of the Novel’s now recognized shortcomings, scholars of the eighteenth century continue to feel the truth of Marina MacKay’s claim that Watt’s book is “unusual among literary-critical classics because it continues after almost sixty years to elicit serious engagement rather than the conscientious citation . . . appropriate to the period piece” (17). Watt may have misidentified the spatial and temporal beginnings of the novel, eighteenth-century critics now agree, but his book itself has become a point of beginning in English studies, an origin not only of eighteenth-century literary criticism, but also of what scholars of other periods and languages know of the eighteenth-century novel. ...

Watt fashioned in The Rise of the Novel, its blemishes notwithstanding, an original poetics of the novel, one that helped establish the English eighteenth-century novel as more than an imperfect precursor of a more achieved artistic form yet to come. Against the negative appraisals of F.R. Leavis, Watt’s own teacher, who had excluded the eighteenth-century novel almost entirely from his “Great Tradition,” Watt reclaimed the eighteenth-century novel for literary history, anchoring his appraisal of its structural features in “the habits of mind and culture that began in seventeenth-century Europe,” ... Influentially, and controversially, Watt defined “novels” as fictional eighteenth-century narratives characterized by “formal realism,” that is “the premise, or primary convention, that the novel is a full and authentic report of human experience.” For Watt, the rise of the novel and the rise of the individual were intertwined: “Philosophically,” he argued, “the particularizing approach to character resolves itself into the problem of defining the individual person.”- Ala Alryyes. Theorising the Novel on the River Kwai, Eighteenth-Century Studies, Volume 54, Number 1 (Fall 2020): pp. 193-201.

Margaret Anne Doody. The True Story of the Novel. 1996. Fontana Press. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.

~

Margaret Doody's provocative book represents the first trumpet blast of dissent against Wattsian orthodoxy. Having extended her reading to the Classical Romances of the Greek and Latin tradition, she points out the difficulty of denying them the title of "novel". There are certainly flaws in her approach: her tendency to generalise often leads her astray, but the book as a whole is hugely stimulating, and well worth a read as a corrective to Ian Watts' somewhat reductive certainties.

Critical reactions:

The title of this critical analysis of the endurance of novelistic tropes from earliest Greek and Roman stories through the permutations of Western fiction is not ironic, despite the insinuation of being a 'true' history in the manner of the eighteenth century. Doody argues that 'what we know of the Novel of antiquity affects and redefines novels of a much later date,' and this revaluation of the origins of the novel 'may disturb our vision of the Western novel altogether.' In an attempt to show the continuity of ancient and modern, Doody argues that the novel owes little debt to Christian myths and is not the product of emergent capitalism in the modern period. ... The patterns set forth in Greek and Roman fiction (apparitions of goddesses, letter scenes, portraiture, and so forth) bear some resemblance to latter-day novels, and Doody's wide-ranging references bring out surprising and unexpected connections between forgotten and familiar texts, but The True Story of the Novel levels differences among hundreds of tales and frequently makes the twentieth century and other periods seem oddly like the ancient world. A passion for stories - why people invent consolatory, allegorical, or romantic tales - underlies the numerous intercultural references of The True Story of the Novel: 'Any culture that needs to deal with cultural pain, multiplicity, and confusion may have to employ allegory of some kind, if only to make its needs and pain known to itself.'- Allan Hepburn. University of Toronto Quarterly, Volume 67, Number 1 (Winter 1997/98): pp. 141-142.

J. Paul Hunter in Before Novels [1990] expresses a sense that getting rid of the categories "Novel" and "Romance" would be "dangerous." He expresses a fear of a "new literary history built thoughtlessly on the rubble of the old" (4: my emphasis). A change in the categories would be a kind of bomb, reducing structures to leveled rubble and encouraging the mushrooming of jerry-built hutments. ...I think that that gives some idea of what Doody was up against when she published her book in the mid-nineties. Most professors have already written their "Rise of the Novel" lectures and course-notes, and few want to dust them off and reconsider them unless they absolutely have to.

When I gave a talk on the early novels and their influence on eighteenth-century literature at a meeting of the American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies in Providence, R.I., in April 1993, I was asked during the question period "why I wanted to bash everything down to one level?" I had not hitherto thought of my thesis in that way, but I could see that, to anyone used to the Rise of the Novel as a story of hierarchy and spatial erection, my narrative could seem like a loss of attributed eminence. I tried to reply that my own spatial metaphor was different - I saw it in terms of leaping over a paddock fence and escaping into a larger space. [p.529]

I myself have noticed a glazing-over of the eyes among some of my colleagues when I suggest to them that any true understanding of the novel must take not simply Pamela, Robinson Crusoe and Don Quixote into account, but also the four classic Chinese novels (The Three Kingdoms, The Water Margin, Journey to the West and the Red Chamber Dream), as well as the Genji - not to mention the Arabian Nights and the Sanskrit Ocean of the Streams of Story (both of which have a number of novel-length stories incorporated within them).

I can therefore sympathise with how Doody felt when she informed her scholarly audience that they couldn't really begin to comprehend the "bourgeois novel" they'd all devoted so much time to without a much more intimate knowledge of Apuleius, Chariton, Heliodorus, Longus, Lucian and Petronius. Goethe and Fielding knew these texts well - can their latter-day interpreters really afford not to?- Jack Ross. The True Story of the Novel, The Imaginary Museum (3 August 2013)

La Pensée du roman. Paris: Gallimard, 2003.

The Lives of the Novel: A History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

~

Thomas Pavel's book is the only one in this list which I haven't read through - or at least dipped into extensively. His thesis, as argued below, certainly sounds like a provocative one, though whether it can really account for the immense variety of phenomena we're still forced to group under that the single term "the novel" remains debatable.

Critical reactions:

This book is a history of the novel from ancient Greece to the vibrant world of contemporary fiction. Thomas Pavel argues that the driving force behind the novel’s evolution has been a rivalry between stories that idealize human behavior and those that ridicule and condemn it. Impelled by this conflict, the novel moved from depicting strong souls to sensitive hearts and, finally, to enigmatic psyches. Pavel makes his case by analyzing more than a hundred novels from Europe, North and South America, Asia, and beyond.- Sophie Franklin. LSE Review of Books (26 January 2014)

According to Pavel, the earliest novels were implausible because their characters were either perfect or villainous. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, novelists strove for greater credibility by describing the inner lives of ideal characters in minute detail (as in Samuel Richardson's case), or by closely examining the historical and social environment (as Walter Scott and Balzac did). Yet the earlier rivalry continued: Henry Fielding held the line against idealism, defending the comic tradition with its flawed characters, while Charlotte Brontë and George Eliot offered a rejoinder to social realism with their idealized vision of strong, generous, and sensitive women. In the twentieth century, modernists like Proust and Joyce sought to move beyond this conflict and capture the enigmatic workings of the psyche.

Pavel concludes his compelling account by showing how the old tensions persist even within today's pluralism, as popular novels about heroes coexist with a wealth of other kinds of works, from satire to social and psychological realism.

Steven Moore. The Novel: An Alternative History, Beginnings to 1600. New York & London: The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010.

Steven Moore. The Novel: An Alternative History, 1600 to 1800. Bloomsbury Academic. New York & London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2013.

~

Steven Moore's immense two-volumed compilation of mini-essays on virtually every novel potentially worthy of the name immediately superseded the efforts of earlier, less industrious critics. His intensely colloquial, rather self-satisfied tone of voice can pall at times, but his sheer erudition redeems all faults of execution (so far as I'm concerned, at any rate). Anyone who claims they could read this book without learning something new from almost every page would have to be knowledgeable beyond normal measure.

Critical reactions:

Encyclopedic in scope and heroically audacious, The Novel: An Alternative History is the first attempt in over a century to tell the complete story of our most popular literary form. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the novel did not originate in 18th-century England, nor even with Don Quixote, but is coeval with civilization itself. After a pugnacious introduction, in which Moore defends innovative, demanding novelists against their conservative critics, the book relaxes into a world tour of the pre-modern novel, beginning in ancient Egypt and ending in 16th-century China, with many exotic ports-of-call: Greek romances; Roman satires; medieval Sanskrit novels narrated by parrots; Byzantine erotic thrillers; 5000-page Arabian adventure novels; Icelandic sagas; delicate Persian novels in verse; Japanese war stories; even Mayan graphic novels. Throughout, Moore celebrates the innovators in fiction, tracing a continuum between these pre-modern experimentalists and their postmodern progeny.

Irreverent, iconoclastic, informative, entertaining - The Novel: An Alternative History is a landmark in literary criticism that will encourage readers to rethink the novel.

Steven Moore's is a majestic work, long in the inception, and hitting pretty much all the right themes for me.

I salute him as a master as well as a kindred spirit (trash-talking, irreligious, fundamentally dirty-minded, and - above all - addicted to complex experimental fiction), and would therefore highly recommend both of his volumes: but particularly the first ...- Jack Ross. Acquisitions (10): Steven Moore. A Gentle Madness (12 October 2013)

John Sutherland. Lives of the Novelists: A History of Fiction in 294 Lives. London: Profile Books Ltd., 2011.

~

Whatever his larger aspirations for it, it's hard to see John Sutherland's vast book as much more than one of those biographical dictionaries which used to be so indispensable to library-bound researchers in the days before the internet. It's interesting to see that his somewhat dilettantish approach to the subject received such ready acceptance by the normally exigent Guardian, whereas Schmidt's more far ambitious work got a caning from them. Insiders and outsiders, perhaps? Jonathan Bate in the Telegraph is rather less accommodating:

Critical reactions:

The intention is to offer “A history of fiction in 294 lives”, paying as much attention to bestsellers and “genre” fiction (detection, sci-fi, romance) as to enduring classics and “literary” novels. Each of the brief lives is headed by a provocative quotation by or about the author in question, and concluded with a little list offering “FN” (full name), “Biog” (recommended biography) and “MRT” (Most Read Text). It is not clear on quite what basis, and with what usefulness, Sutherland has determined that the MRT of Charles Dickens is Great Expectations rather than Oliver Twist or A Christmas Carol.

Whereas Johnson’s Lives of the Poets moved from overview of the life to measured critical insight, Sutherland’s Lives of the Novelists is heavy on biographical anecdote – especially when it comes to sexual activity and alcoholic intake – but distinctly light on literary analysis. Thus, Harold Robbins gives Sutherland the opportunity to tell his readers that “Screwing was off the menu in his last years, after – high on cocaine – he fell in his shower and shattered his pubic bone,” whereas the essay on Samuel Beckett concludes with the considered judgment that the Nobel Prize-winner’s later fiction consists of “gnawing the same old bones into ever more boniness”. ...

Who does he really admire? To judge by the simple criterion of word count per life, the answer would appear to be Ian Fleming.

The book is not without its pithy quotes and witty moments. It’s worth dipping into if you are in search of a forgotten bestseller or a simple biographical answer to the question of why certain authors (Rex Warner, say, or Malcolm Lowry) were one-hit wonders.

But it is emphatically not what it says on the cover. How could “a history of fiction” be entirely anglophone? Roll over Flaubert, Balzac, Proust, Tolstoy and Mann.

A true history of the novel could not be written in the form of brief lives alone. It would need to give much more attention to the development of styles and conventions, to the dialogue between writers and their predecessors and, above all, to readers as well as writers.

Sutherland’s coverage of pre-Victorian fiction is pitifully thin, yet it was in the 18th century that the novel emerged as the most popular literary form the world had ever seen. Women writers and women readers – most of them ignored by Sutherland – played a huge part in the story.- Jonathan Bate. The Telegraph (23 November 2011)

The author's own not so guilty pleasures are everywhere apparent. Sutherland is a sucker for crime fiction and doesn't care who knows it. Elmore Leonard, whose 10 rules for writing have been widely tweeted in the month since his death, is introduced, for example, as "the greatest American novelist never to be mentioned in the same breath as 'Nobel prize'". Leonard, you guess, would have enjoyed Sutherland's book, which is to literary biography something like his novels were to literary fiction. That is to say Sutherland "leaves out the parts that readers tend to skip" and is rarely seduced by "hooptedoodle".- Tim Adams. The Guardian (15 September 2013)

Michael Schmidt. The Novel: A Biography. Cambridge, Mass & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

~

Unlike Sutherland's, Michael Schmidt's immense book invites disagreement. The way in which he breaks up his basically chronological arrangement with sudden intrusions from the contemporary - following Sir Philip Sidney, John Bunyan and Aphra Behn with Zora Neale Hurston, for example - is no doubt intended to liven up and make relevant some otherwise potentially dry-as-dust precursors to the modern novel. This can be disconcerting at times, and as his Guardian reviewer remarks below: "He doesn't do it in reverse, inserting remote ancestors into 20th-century chapters." It certainly shows a determination to keep his story relevant, engagée, however, which is surely a good thing. Isn't it?

Critical reactions:

The 700-year history of the novel in English defies straightforward telling. Geographically and culturally boundless, with contributions from Great Britain, Ireland, America, Canada, Australia, India, the Caribbean, and Southern Africa; influenced by great novelists working in other languages; and encompassing a range of genres, the story of the novel in English unfolds like a richly varied landscape that invites exploration rather than a linear journey. In The Novel: A Biography, Michael Schmidt does full justice to its complexity.

Like his hero Ford Madox Ford in The March of Literature, Schmidt chooses as his traveling companions not critics or theorists but 'artist practitioners', men and women who feel 'hot love' for the books they admire, and fulminate against those they dislike. It is their insights Schmidt cares about. Quoting from the letters, diaries, reviews, and essays of novelists and drawing on their biographies, Schmidt invites us into the creative dialogues between authors and between books, and suggests how these dialogues have shaped the development of the novel in English.

Schmidt believes there is something fundamentally subversive about art: he portrays the novel as a liberalizing force and a revolutionary stimulus. But whatever purpose the novel serves in a given era, a work endures not because of its subject, themes, political stance, or social aims but because of its language, its sheer invention, and its resistance to cliche - some irreducible quality that keeps readers coming back to its pages.- Goodreads (12 May 2014)

Schmidt ... [diversifies] a generally chronological approach with the insertion of novelists from much later. (He doesn't do it in reverse, inserting remote ancestors into 20th-century chapters.) His essays on individual novelists are acute, draw interesting parallels, have little shame about talking about biographical details in a very old-fashioned way – "There are touches of [John Dickens's] wife in Mrs Micawber". The problem is that we have very little sense of how the novel develops from within. [E. M.] Forster's point about novelists sitting in a circle was a commendable attempt to avoid any Whiggish sense that they are somehow improving on their predecessors. What it, and Schmidt, fail to account for is a real sense of how writers are always polishing and refining on the technical insights of their predecessors. George Eliot and even Flaubert have a loose approach to point-of-view: we can see them hopping from mind to mind within a scene. A generation later, Henry James is absolutely strict: we never find out what more than one character is thinking without a firm formal break. We may actually prefer the looser approach of the earlier generation, but there is no doubt that a subsequent generation has embarked on a project of refinement and development. This is the proper subject of a history of the novel. ...

It's an engaging and interesting book, written by an acute reader who rightly trusts his own taste and has read more than most of us will ever get through. What I would really like is for Schmidt to take a deep breath, set aside the lives of the great, their individually extraordinary natures, and finally write a 200-page book about how the flavours and techniques of the novel changed from time to time: how in 1750 the fashionable novel was a series of intimate, richly adjectival letters about not going to bed with a man, and in 2014 it was a present-tense first‑person screed about sitting in a characterless airport without a single metaphor within reach. There must be some kind of answer.- Philip Hensher. The Guardian, 1434 (28 August 2014)

The True Story of the Novel: Introduction (2013-2014):

- The Eastern Frame-Story (25/8/13)

- The Greek and Roman Novel (4/9/13)

- The Japanese Monogatari (10/10/13)

- The Medieval and Renaissance Romance (24/10/13)

- The Sagas of Icelanders (18/12/13)

- The Chinese Novel (22/12/13)

- The Modern Novel (2/1/14)

~

Back when I was an Academic, I worked on a series of perhaps needlessly ambitious non-fiction projects.

Let's see, I started off in the early 1990s with a study of the 1001 Nights and Comparative Literature, as a change of pace after finishing my Doctorate on South American literature. The eventual result was a few articles and conference papers, collected on my website Scheherazade's Web. My projected book on the subject never saw the light of day, however.

After that I got interested in comparative studies of the origins of prose fiction, an even more far-reaching and less practical area of study. This ended up, in skeleton form, in the series of bibliographically focussed blogposts listed above.

My final such project was a study of New Zealand Science Fiction. In that case the book actually got written, only to be rejected by a series of publishers. It, too, ended up as the website NZSF.

Thank God for in the internet, I say. All that work would have been wasted otherwise, and I still get hits on all of those sites, probably mostly from students hoping to crib facts for their latest essay.

Critical reactions:

On The Greek and Roman Novel (4/9/13), Katherine Dolan said...Magnificent, as usual. We found a copy of Collected Greek Novels and I started reading "The Ass" to John but it was too gory. I couldn't stop being horrified by how you're clearly supposed to think the poor animal being tortured or frightened out of its wits is just the funniest thing in the world.On The Medieval and Renaissance Romance (24/10/13), Anonymous said...

4 September 2013 at 15:16I have so far only read the post about the 1001 Nights translations, and this one, but this blog looks like a goldmine. Thanks a lot for maintaining it all those years!On The Sagas of Icelanders (18/12/13), Kerry Kirwan said...

31 January 2024 at 00:45Hi Jack. Nice study, which I've just come across.On The Modern Novel (2/1/14), Michael Morrissey said:

I don't know if you remember me but I studied Travel Writing at Albany with you in 2012 and my final assignment was about my trip to Iceland in search of Halldor Snorrason.

I'm about to embark on my Masters in History and my thesis is going to be a medieval travel story about Halldor and a couple of other eleventh century Icelandic travellers.

20 March 2016 at 13:22Congratulations to Jack Ross for his erudite summary of the novel's development. I was notionally aware of the long history of the novel which goes back 2000 plus years - but not in the detail offered here.

On a more personal note I also had Dr Jonathan Lamb as a lecturer on the modern novel a few years before Jack (around 1977). He and his colleagues Professor Michael Neill and Mr Sebastian Black presented a series of lectures on writers like Garcia Marquez, Berger, Lowry, Mailer, Sartre, Borges and a few others I cannot recall. Lamb's lectures were so tightly constructed that students would write down virtually every word. ...

•

- category - Literature, Language & Philosophy: Literature & Philosophy